Storytelling in a Technical World

At first glance, the idea of storytelling in Safety Critical Task Analysis (SCTA) might raise eyebrows. After all, isn’t SCTA supposed to be a serious, technical, and objective process? Aren’t we dealing with potential major accident hazards, detailed risk assessments, and objective control measures? Why would something as subjective and emotional as “storytelling” have any place in this context?

This potential tension is precisely why we need to address it head-on. The technical world of process safety, with its engineering controls, quantitative risk assessments, and formal procedures, often leaves little room for the human narrative. Yet paradoxically, it’s the human element that is frequently at the heart of both incidents and resilience in our systems.

Storytelling isn’t a replacement for technical rigor—it’s a complement to it. Stories help us explore previous experiences and expertise, visualize sequences of events that haven’t yet transpired, and create a social and collaborative environment where different stakeholders can work together towards shared goals.

In this blog, we’ll explore how narrative approaches can enhance and strengthen the SCTA process, making it more effective, more inclusive, and ultimately more successful in its goal of identifying and managing human factors risks.

The Narrative Arc of SCTA: Different Stories for Different Stakeholders

One of the first things to recognize is that doing SCTA itself represents different narrative arcs for different stakeholders within the organisation. Why do SCTA in the first place?

- For leadership, applying SCTA resonates well with stories of adopting best practice and shareholder value—reducing risks that could lead to costly incidents, protecting the company’s reputation, and demonstrating commitment to safety.

- For management and engineers, it’s a story about comprehensive risk assessment—filling a gap that traditional hazard identification methods might miss, by addressing the human components that are often the most variable and challenging to control.

- For frontline staff, SCTA represents a story of creating a safer workplace—making their daily tasks more manageable, reducing stress, and ensuring everyone goes home safely at the end of each shift. SCTA allows them to be heard and share their expertise.

SCTA serves as a meeting point for these different narratives, allowing them to inform and enrich each other. The power of story as a fundamental human communication tool helps bridge these different perspectives, creating a shared understanding that purely technical approaches might miss.

Setting the Scene: Stories as Ice-Breakers and Normalisers

When we conduct SCTA workshops, one of our most powerful techniques involves sharing stories to create psychological safety. We might begin with:

“At another site we worked with, operators were dealing with a complex valve arrangement. One operator accidentally operated the wrong valve because they looked identical and were positioned close together. Fortunately, there was a pressure safety valve downstream that prevented any major incident.”

Stories like this serve multiple purposes:

- They normalize error (“To err is human”)

- They demonstrate that other sites face similar challenges

- They show that sharing these experiences is valued and not punished

- They illustrate how the analysis can lead to practical improvements

This narrative approach breaks down barriers, particularly for frontline staff who might initially be hesitant to discuss mistakes or workarounds for fear of repercussions. When participants see that the focus is on learning and improvement rather than blame, the quality of information shared increases dramatically.

Another narrative tool we use to normalise error in our SCTA training and workshops is relating everyday errors with more serious errors in the industrial context. James Reason, a master communicator in our field, also used this technique which can be seen in this BBC documentary. Here, the same psychological mechanisms that underlie mistakes in the kitchen also underlie fatal errors in the workplace – our CEO, Dr David Embrey, also features in the video.

James died recently. I was talking to David just the other day and he shared many fond personal memories with him. They and others played a major role in the formative years of Human Factors risk management following Three Mile Island and other disasters around the 70’s and 80’s. Many people on LinkedIn who met and had not met James shared their own stories, and how his insights and stories impacted their own lives and career choices.

Telling stories about accidentally putting a tea bag into the washing machine rather than a cleaning tab or ruining a Thai green curry because the recipe is poorly written can help people gain insight, laugh, relax and see the ‘human’ in the process.

One of the key insights I got from the book Interviewing Users was that there is often a tipping point when talking to people where we switch from a Q&A mode to a story telling mode, the latter generally being a much richer source of data. Telling our own stories aids this process.

The Narrative Structure of SCTA Analysis

The analysis itself follows a narrative structure that helps ensure its completeness and coherence.

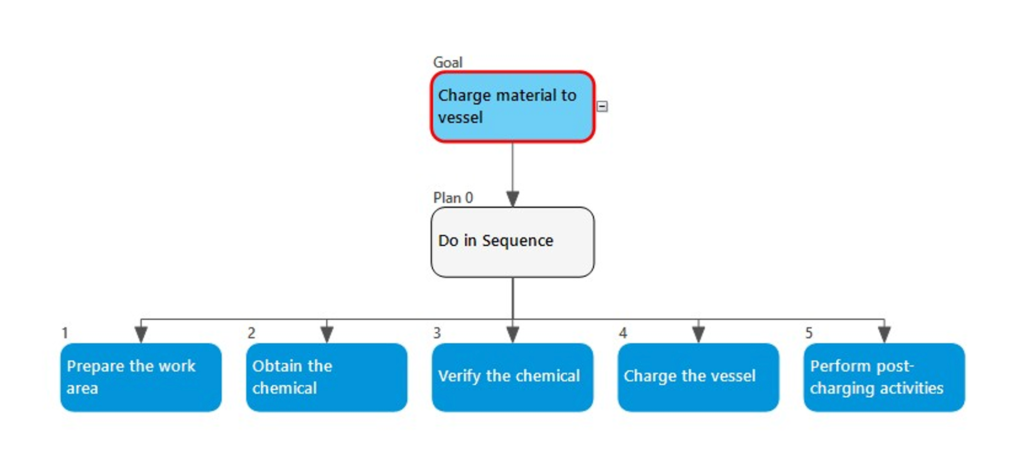

The Hierarchical Task Analysis (HTA) works to tell and share stories about how people perform the work. The top level of the HTA almost act like chapter headings that tell the story of the task. For instance, in a chemical charging task, our chapter headings might include “Preparing the work area,” “Obtaining the chemical,” “Verifying the chemical,” “Charging the vessel,” and “Post-charging activities.” Each chapter has its own narrative flow while contributing to the overall story of the task.

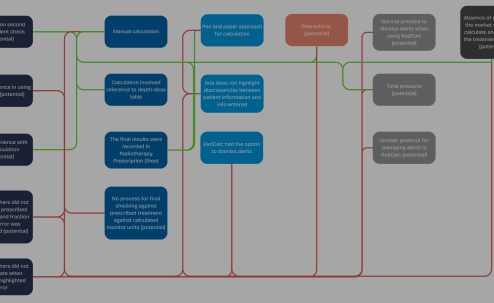

The SCTA Data Grid (the table that captures failure modes, consequences, controls, PIFs, and improvements) must maintain narrative consistency across its elements. For example, if we identify a failure mode of “Operator selects wrong chemical,” the error description, consequence, and PIFs should all align with that specific scenario. Gaps or glitches in this narrative can indicate weak points in the analysis.

- A gap might be where information is missing, e.g. controls have not been identified.

- A glitch might be where inconsistencies are found, e.g. a lapse (error of omission) is identified for when two chemicals are confused (error of commission).

Failure modes themselves serve as narrative devices to explore different “plots” of what could go wrong. “What if the step is omitted?” “What if it’s done incorrectly?” “What if it’s done on the wrong object?” Each represents a different storyline that might unfold, helping us to comprehensively map potential vulnerabilities.

The Work-as-X Stories: Bridging Imagination and Reality

Perhaps the most valuable contribution of a narrative approach is in bridging the gap between different perspectives on work:

- Work-as-imagined: The official procedural story, how management and engineers believe the task is performed

- Work-as-done: The lived experience story, how operators actually perform the task day-to-day

- Work-as-disclosed: What people are willing to share about their work practices, which may differ from both of the above

SCTA creates a dialogue between these different stories. For example, a procedure might state that two operators should verify a chemical before charging (work-as-imagined), but in practice, staffing constraints might mean this rarely happens (work-as-done). The workshop environment allows this discrepancy to be disclosed and addressed.

By treating these different perspectives as equally valid parts of the overall story, rather than labelling one as “correct” and others as “deviations,” we create a richer understanding of the actual task and its vulnerabilities.

The Full Spectrum of Operational Stories

During our workshops, we encounter many types of stories, each offering unique insights:

- Success stories: “When the level indicator failed last month, the operator noticed something wasn’t right because the pressure gauge was reading differently than expected. Their experience allowed them to catch the problem before it escalated.”

- Near-miss stories: “We once almost charged the wrong chemical because the two drums looked nearly identical. Now we always double-check the batch numbers.”

- Failure stories: “Three years ago, we had a small spill because the connection wasn’t properly sealed. That’s why we now have a formal verification step.”

- Innovation stories: “The maintenance team developed a color-coding system for these valves because they’re so easy to confuse.”

- Resilience stories: “When we’re short-staffed, the supervisor always prioritizes being present for the critical verification steps.”

Each type of story reveals different aspects of the system’s vulnerabilities and strengths. By collecting and analysing a diverse range of narratives, we develop a more comprehensive understanding of the task than would be possible through procedural review alone.

These different types of story engage with performance variability in practice. This is precisely what emerges during a well-facilitated SCTA. Sometimes we discover informal adaptations that teams have implemented but never documented in procedures. Other times, tales of near misses (like operators noticing unusual pressure gauge readings) open up discussion about less obvious errors that were caught thanks to knowledge and experience. These discussions reveal where such learning could be maximized through improved training or competence arrangements if explored more thoroughly.

Creating an environment where these types of stories naturally emerge is crucial, because this information typically isn’t being documented or acted upon elsewhere in the organisation. These stories often reveal informal controls or positive Performance Influencing Factors that deserve recognition. SCTA serves as a vehicle for extracting this valuable knowledge and getting it recognized or formalized before it’s lost when experienced staff move on or retire.

Language Matters: The Vocabulary of Story

The language we use significantly influences what stories get told. This is why we’re thoughtful about the terminology in our workshops:

We prefer “non-compliance” over “violations” when discussing procedural deviations. “Violation” carries punitive connotations that might silence important disclosures, while “non-compliance” opens the door to exploring why procedures aren’t followed—perhaps because they’re impractical, outdated, or don’t reflect real conditions.

Similarly, we talk about “performance influencing factors” rather than “error causes” to avoid blame and focus on system conditions that make errors more or less likely. Error traps are where there is a configuration of poor PIF conditions that almost make an error likely, however error traps are not synonymous with PIFs. PIFs are a richer concept.

By creating a non-judgmental narrative environment through careful language choices, we encourage more authentic and useful storytelling from all participants.

Stories as Organisational Learning

SCTA workshops provide a unique platform for knowledge exchange between operators, supervisors, engineers, and management. Stories shared during these sessions often contain valuable insights that might otherwise remain siloed within specific teams or shifts.

For example, during a workshop representatives from two shifts complained about mislaying certain bits of kit during maintenance. Someone from a third shift did not recognise the problem as they had a bag to keep these items organised. Through sharing the story the other shifts now benefit from this improved practice, better performance and less frustration. The workshop allowed this knowledge to be recognized, evaluated, and incorporated into formal procedures.

These shared storytelling opportunities foster a positive safety culture by:

- Validating frontline experience

- Distributing knowledge across organisational boundaries

- Creating a collaborative approach to safety

- Maintaining organisational memory when experienced staff leave

Case Example: The Power of Story in SCTA

A specific example demonstrates how storytelling enhanced an SCTA for a tanker offloading task at a chemical processing facility.

During the workshop, one operator casually mentioned, “The tanker drivers know which connection to use, so we don’t worry too much about supervising the connection.” This story—told almost as an aside—revealed a critical dependency on external knowledge that created vulnerability in the system.

Further exploration through targeted questions uncovered additional stories:

- A near-miss where a driver had connected to the wrong inlet at a different site

- How the operator is forced to trade-off supervising the connection with monitoring another safety critical task

- A historical incident at another site involving a similar situation

These narratives painted a picture that wouldn’t have emerged from procedural review alone. The analysis led to several improvements:

- Clear labelling of all connection points

- A review of the operators workload and expectations

- Updated training that addressed this specific vulnerability

Without the storytelling approach, this dependency might have remained hidden until a more serious incident occurred.

Practical Guide: Enhancing Your Story-Gathering Skills

To effectively integrate storytelling into your SCTA process:

- Ask open-ended questions that invite narrative responses:

- “Can you tell me about a time when this task was particularly challenging?”

- “What’s the most unusual situation you’ve encountered while doing this?”

- “How did you learn to do this task?”

- Create environments conducive to storytelling:

- Use locations where people feel comfortable (not management offices)

- Include peers rather than just supervisors in group discussions

- Actively acknowledge and appreciate shared experiences

- Capture stories effectively:

- Document narratives in participants’ own words when possible

- Note context and conditions that made the story significant

- Connect stories to specific task steps and potential failure modes

- Analyse stories for patterns:

- Look for common themes across different narratives

- Identify inconsistencies between stories and formal procedures

- Note successful adaptation strategies that could be formalised

Conclusion: SCTA as a Collective Story-Making Process

At its best, SCTA is not just an analytical method but a collective story-making process. It brings together diverse perspectives to create a shared narrative about critical tasks—one that acknowledges complexities, validates experiences, and works toward a safer future.

The stories gathered during SCTA don’t just inform the immediate analysis; they become part of the organisation’s safety culture. They transform abstract risks into concrete, relatable scenarios that people remember and learn from.

So, while storytelling might initially seem at odds with the technical rigor of safety analysis, it’s actually an essential component that makes SCTA more human-centred, more comprehensive, and ultimately more effective.

Embracing the power of story in our approach to human factors, we acknowledge that safety isn’t just about procedures and controls—it’s about people, their experiences, and the narratives they construct to make sense of their work. And in doing so, we create safer systems that benefit everyone involved.

Find out more about Safety Critical Task Analysis (SCTA) here: https://www.humanreliability.com/human-factors/safety-critical-task-analysis-scta/

Interested in learning more, do our flagship course on Safety Critical Task Analysis (SCTA): https://the.humanreliabilityacademy.com/courses/human-factors-SCTA