THE PARABLE OF THE ANT Imagine, if you will, a warm summer morning on a beach. The tide has receded, leaving behind a glistening expanse of sand dotted with pebbles, shells, and the occasional piece of driftwood. Near the edge of the beach stands a scientist, notebook in hand, observing something curious. Day after day, the scientist returns to the same spot to watch a colony of ants that has made its home beneath a piece of driftwood. What first caught the scientist’s attention was the remarkable transformation in the ants’ behaviour over time. On the first day, an ant emerges from the colony and begins what appears to be a random journey across the sand. She zigzags unpredictably, backtracks frequently, circles aimlessly, and wanders in seemingly pointless directions. After nearly thirty minutes of this erratic exploration, she stumbles upon a piece of fruit left behind by beachgoers. She takes a small fragment and begins her journey home – a journey just as wandering and inefficient as her outward path. However, another ant emerges, and something interesting happens. This ant’s path is still irregular, but noticeably less random than the day before. She finds the fruit more quickly – in about twenty minutes – and her return journey shows fewer unnecessary detours. By the fifth day, the transformation is remarkable. Ants from the colony now march in nearly straight lines directly to the food source and back again. What once took thirty minutes of wandering now takes barely three minutes of purposeful travel. “Fascinating,” notes the scientist. “These ants have learned the location of the food. Through trial and error, they’ve developed a mental map of their environment and the optimal path to resources. We’re witnessing adaptive learning behaviour. The ants are becoming smarter.” The scientist presents these findings at a conference, where colleagues nod in agreement. The ability of the ants to improve their navigation demonstrates sophisticated learning capabilities – perhaps even a rudimentary form of intelligence. The colony appears to be developing collective wisdom, with each ant somehow becoming smarter, more efficient, more purposeful in its movements. But then another scientist joins the study, bringing specialized equipment that reveals something unexpected: the invisible chemical trails of pheromones laid down by the ants. And suddenly, the explanation shifts dramatically. The ants haven’t changed at all. The beach has. What looked like learning was actually the gradual accumulation of pheromone trails. Each ant follows the same simple rules from day one to day five: explore randomly, when you find food bring it back, and leave a chemical trail along your path. When another ant encounters a pheromone trail, she’s more likely to follow it, and when she successfully finds food, she reinforces that trail with her own pheromones. The more ants travel a successful path, the stronger the chemical signal becomes. Over time, the optimal route emerges not through any individual ant becoming smarter, but through the collective modification of the environment. The beach itself has been transformed with an invisible infrastructure of chemical signals that guide even the most novice ant efficiently to food and back. Most remarkably, new generations of ants born into the colony inherit this environmental wisdom. An ant hatched today benefits from pathways established by predecessors long gone. She hasn’t learned anything her ancestors didn’t know—she’s simply born into a world that has been restructured to make successful navigation almost inevitable. This humble colony reveals something profound about achievement and progress. What appears to be individual learning or intelligence often emerges from the accumulation of small environmental changes that guide behaviour in increasingly effective ways. The parable extends powerfully to human civilization. We modern humans share essentially the same biology, the same basic cognitive machinery, as our ancestors from thousands of years ago. Yet our achievements far surpass theirs – not because we’re individually smarter, but because we inherit an environment rich with accumulated knowledge, technology, and cultural practices built up over generations. Our buildings, tools, books, institutions, and digital networks function like the ants’ pheromone trails—they structure our world in ways that guide behaviour and support achievements far beyond what any individual could accomplish alone. And herein lies the wisdom that transforms fields from education to design/engineering: To understand and improve human performance, we must look beyond the individual to the environment that shapes their path. The complexity and achievement we observe often emerges not from individual brilliance alone, but from the accumulation of environmental modifications that guide behaviour in increasingly effective ways. |

Herbert Simon and The Sciences of the Artificial

Herbert Simon’s Parable of the Ant is a thought-provoking metaphor that appears in his 1969 book “The Sciences of the Artificial.” The parable is used to illustrate an important concept about complexity and behaviour.

In the parable, Simon describes an ant making its way across a beach. The ant’s path appears complex and irregular as it navigates around pebbles, dips in the sand, and other obstacles. However, Simon points out that the complexity we observe in the ant’s path doesn’t necessarily reflect complexity in the ant’s decision-making process or internal navigation system.

The key insight is that the apparent complexity of the ant’s behaviour is largely a reflection of the complexity of the environment it’s navigating, rather than the complexity of the ant itself. The ant may be following relatively simple rules (like “go around obstacles” or “head toward a certain point”), but when these simple rules interact with a complex, irregular environment, the resulting path looks intricate and sophisticated.

Simon uses this parable to make a broader point about how we interpret complex behaviour in systems: what appears to be complex behaviour might not require a complex explanation but might instead emerge from the interaction between relatively simple decision rules and a complex environment. As humans we create/design some of our environment, so to study behaviour is to study this man-made environment: Sciences of the Artificial.

Edwin Hutchins and Cognition in the Wild

Edwin Hutchins also used Simon’s ant parable, but he extended and reinterpreted it in significant ways in his influential work “Cognition in the Wild” (1995).

Hutchins took Simon’s parable and developed it further to support his theory of distributed cognition. Some differences in Hutchins’ interpretation:

- Distributed cognition focus: While Simon used the parable to show how complex behaviour could emerge from simple rules interacting with a complex environment, Hutchins emphasized how cognition is distributed across the environment and not just inside the individual’s head.

- Navigation metaphor expansion: Hutchins applied the parable specifically to navigation (which was fitting since his research involved studying navigation teams on naval vessels). He suggested that human navigation, like the ant’s, depends heavily on structures in the environment.

- Cultural and social dimensions: Hutchins added cultural and social layers to the interpretation. He argued that humans, unlike ants, create and maintain their own environmental structures (like maps, tools, and social organizations) that then shape their cognitive processes.

- Historical accumulation: Hutchins emphasized how humans inherit and build upon environmental structures created by previous generations, creating a kind of “cognitive ecology” that evolves over time.

- Socio-technical systems: While Simon focused on individual behaviour, Hutchins used the parable to explain how complex tasks are accomplished through coordination between people and their tools in socio-technical systems.

Hutchins essentially transformed Simon’s parable from a statement about individual behaviour complexity into a framework for understanding how human cognition works through interaction with cultural artifacts, tools, and other people. His interpretation helped establish the field of distributed cognition, which views thinking as something that happens not just in individual minds but across systems of people and the tools they use.

Studying Workplaces as Cognitive Ecosystems

Ergonomics—derived from the Greek “ergon” (work) and “nomos” (laws)—studies how humans interact with their surroundings to enhance both wellbeing and performance. Much like Simon’s ant navigating the beach, humans navigate their workplaces through a complex interplay between individual capabilities and environmental design.

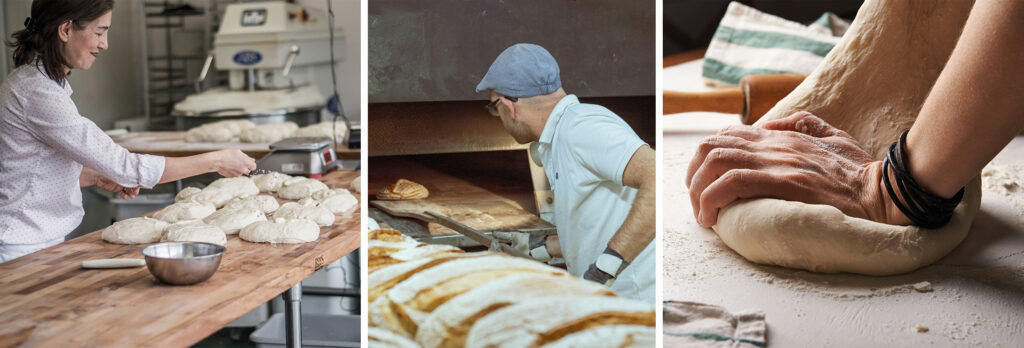

Workplaces represent fascinating cognitive ecosystems that have evolved over generations, gradually accumulating knowledge, tools, and practices that shape human performance. Consider traditional crafts (like the butcher, baker and candlestick maker) that have developed over centuries:

The butcher’s shop contains specialized cutting surfaces, knives designed for specific cuts, and spatial arrangements that facilitate workflow. The experienced butcher moves with efficiency not because they’ve fundamentally changed as a person, but because they operate within an environment optimized through countless iterations across generations. The placement of tools, the height of the counter, and even the vocabulary used to describe cuts represent environmental modifications that guide behaviour and reduce cognitive load.

Similarly, a baker’s workspace encompasses specialized tools like proofing baskets and scoring blades, along with environmental markers such as timers and visual cues for dough readiness. What appears as expert intuition often relies heavily on these environmental scaffolds that have evolved to support complex work.

Even the candlestick maker’s craft depends on a workspace organized around structured processes, with specialized moulds, temperature-appropriate workspaces, and tools designed specifically for handling hot wax. The seemingly simple task of making candles becomes efficient through this carefully curated environment.

In more modern and complex domains, Human Factors practitioners investigate similar relationships across diverse settings—from aircraft cockpits to chemical plants, from surgical theatres to scientific laboratories. When we analyse work environments, identify issues, and make recommendations, we’re essentially accelerating the evolutionary process that would otherwise happen gradually through trial and error.

Rather than waiting for the equivalent of ant pheromone trails to develop naturally over time, Human Factors interventions deliberately reshape the cognitive ecosystem to support human performance. We might redesign control panels to match operators’ mental models, improve procedure layout to highlight critical steps, or introduce decision support tools that reduce memory demands.

By understanding workplaces as cognitive ecosystems—beaches to our human ants—we recognize that improving performance often depends less on changing the people and more on optimizing the environment that guides their behaviour. This perspective transforms how we approach everything from interface design to safety management to organisational learning.

A Qualification: Behaviour shapes context

While the Parable of the Ant offers profound insights into how context shapes behaviour, we must acknowledge an important qualification: humans are not ants. The analogy, like all analogies, has its limitations.

Unlike ants, humans possess agency—the capacity to make conscious choices, reflect on their environment, and deliberately shape it. We don’t simply respond to our surroundings; we actively interpret, question, and transform them. This human agency manifests in numerous ways that extend beyond the ant’s algorithmic behaviour.

Consider how people create desire paths—those informal trails worn across lawns or fields where no formal pathway exists. These physical manifestations of human agency represent collective decisions to optimize routes beyond designed walkways. Some organizations fight these shortcuts, installing barriers or signs. Others recognize the wisdom in these emergent patterns and eventually formalize them into official pathways. This interplay between human choice and environmental design illustrates a complexity absent from the ant parable.

In my research on resilience strategies, I’ve documented numerous ways people develop and share innovative approaches to avoid errors and improve performance. Healthcare professionals create clever workarounds for poorly designed electronic systems; operators develop memory aids that complement formal checklists; factory workers adjust standard procedures to accommodate unusual circumstances. These adaptations aren’t random—they represent deliberate responses to environmental constraints, often arising from deep expertise and situational awareness.

This relationship between human agency and environmental structure is what sociologists call structuration (Giddens, 1984)—a reciprocal process where human actions create and modify structures, while those very structures simultaneously shape human behaviour. Unlike our ant protagonist, we both respond to and create the paths we travel in quite a different way.

Sometimes these human-created paths represent positive innovations that organizations should embrace and formalize. Other times, they manifest as violations of important safety rules—shortcuts that compromise critical protections. The human capacity for judgment, unlike the ant’s simple algorithm, requires us to evaluate when adaptations enhance performance and when they undermine it. David Embrey writes more about non-compliance here: https://www.humanreliability.com/2024/11/tackling-procedural-non-compliance-in-the-workplace/

So, while the ant parable powerfully illustrates how context shapes behaviour, the full picture of human performance is more nuanced. Humans are both influenced by and influencers of their environment in an ongoing dialogue. The beach and the ant shape each other.

This qualification doesn’t diminish the parable’s central insight about the importance of environmental design. Rather, it enriches our understanding of human factors by recognizing that people aren’t merely responding to static environments but are active participants in creating them.

Effective human factors work must therefore consider both sides of this equation—designing environments that support human performance while also developing people’s capacity to recognize opportunities for innovation and improvement. We must create beaches that guide behaviour appropriately while acknowledging and sometimes harnessing the human ability to reshape those beaches for the better.

In the end, the most successful organizations recognize that humans are part of the system under study, not separate from it. By embracing both environmental influence and human agency, we can create workplaces that are not only well-designed for current work but adaptive to emerging challenges and opportunities.

Summary: The Wisdom of the Ant’s Path

The Parable of the Ant offers a profound lens through which to view human performance and systems design. As it evolved from Simon’s original insight to Hutchins’ expanded interpretation, the parable reveals two transformative insights that lie at the heart of human factors thinking.

Insight 1: Cognition is distributed across our external environment. What appears as complex behaviour often emerges from the interaction between relatively simple internal processes and richly structured environments. Our thinking doesn’t just happen inside our heads but extends into and through the world around us—the tools we use, the spaces we inhabit, and the information structures we create.

Insight 2: Cognition evolves over time through environments that develop across generations. Like the ant colony’s pheromone trails, human knowledge accumulates in our cultural artifacts, tools, language, and practices. We inherit cognitive environments shaped by countless predecessors, allowing us to achieve what would be impossible through individual learning alone.

As humans, we possess an exceptionally rich cultural heritage embedded in the physical and informational structures that surround us. Our workplaces represent treasure troves of specialized cultural artifacts—from the surgeon’s precisely arranged instrument tray to the pilot’s carefully designed cockpit, from the chef’s kitchen workflow to the control room operator’s interface.

This distributed, cultural view of cognition captures the essence of human factors thinking. While our thinking is undeniably shaped by context, we also actively shape that context through our agency and innovation.

Acknowledgement

This article was drafted with the assistance of Claude AI 3.7 Sonnet.

Stay in touch

If you haven’t signed up to our monthly newsletter and blogs yet then do so here by downloading our handbook: https://www.humanreliability.com/downloads/human-reliability-handbook/

Follow us on LinkedIn here: https://www.linkedin.com/company/human-reliability-associates/

References

Simon, H. A. (2019). The sciences of the artificial (4th ed.). MIT Press. (Original work published 1969)

Hutchins, E. (1996). Cognition in the wild (2nd ed.). MIT Press.

Giddens, A. (1986). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration (Paperback ed.). University of California Press.

Further reading on from me

Resilience Strategies

Furniss, D., Back, J., Blandford, A., Hildebrandt, M., & Broberg, H. (2011). A resilience markers framework for small teams. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 96(1), 2-10.

Furniss, D., Back, J., & Blandford, A. (2012). Cognitive Resilience: Can we use Twitter to make strategies more tangible?. In Proceedings of the 30th European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics (pp. 96-99).

Furniss, D., Robinson, M., & Cox, A. (2018). Exploring resilience strategies in anaesthetists’ work: A case study using interviews and the Resilience Markers Framework (RMF). In Delivering resilient health care (pp. 66-79). Routledge.

Furniss, D., Barber, N., Lyons, I., Eliasson, L., & Blandford, A. (2014). Unintentional non-adherence: can a spoon full of resilience help the medicine go down?. BMJ quality & safety, 23(2), 95-98.

Distributed Cognition

Furniss, D., & Blandford, A. (2010). DiCoT modeling: from analysis to design.

Furniss, D., Masci, P., Curzon, P., Mayer, A., & Blandford, A. (2015). Exploring medical device design and use through layers of distributed cognition: how a glucometer is coupled with its context. Journal of biomedical informatics, 53, 330-341.

Structuration

Furniss, D., Mayer, A., Franklin, B. D., & Blandford, A. (2019). Exploring structure, agency and performance variability in everyday safety: an ethnographic study of practices around infusion devices using distributed cognition. Safety Science, 118, 687-701.