I recently completed the “A Systems Approach to Investigating and Learning From Patient Safety Incident” by the UK’s Health Services Safety Investigation Body (HSIB). The course introduces using a socio-technical perspective on patient safety and highlighted the effectiveness of the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) framework.

In a previous post, I used a Swimlane analysis to examine an incident where a patient received much higher doses of ionising radiation than prescribed. Here, I thought I would revisit the same case study and apply SEIPS as an attempt to explore the systemic factors at play.

Background on SEIPS

Developed by Carayon et al. in 2006, the SEIPS framework posits that adverse events in healthcare arise from how work is organised rather than from individual actions alone. SEIPS divides the healthcare system into six interacting components:

- People

- Job

- Tools and Technology

- Physical Environment

- Organisational

- External

By examining aspects within each component and understanding how these interact, SEIPS allows us to identify systemic issues and redesign flawed processes, improving overall patient safety.

Because of its structured yet practical approach, it has been widely adopted in the healthcare industry to understand and learn from safety incidents. It has also been included as one of the tools within the Patient Safety Learning Response Toolkit.

Case study

In September 2015, a patient diagnosed with a form of bone marrow cancer called multiple myeloma was scheduled for a course of radiotherapy. The treatment prescribed was 400 centiGrays of ionising radiation (in two 200 centiGray beams) for 5 days. Due to an error when calculating the doses and a subsequent misinterpretation within the dose calculation programme, RadCalc, the treatment machine was mistakenly set to deliver 800 centiGrays. The error was detected 11 days after the final treatment, and the patient was exposed to a significantly excessive does of radiation.

*This was a brief summary of the incident. For a detailed account of the sequence of events, please refer to my earlier post – The Swimlane Method: A Case Study to Improve Patient Safety.

Detailed SEIPS Analysis

Initial Categorisation

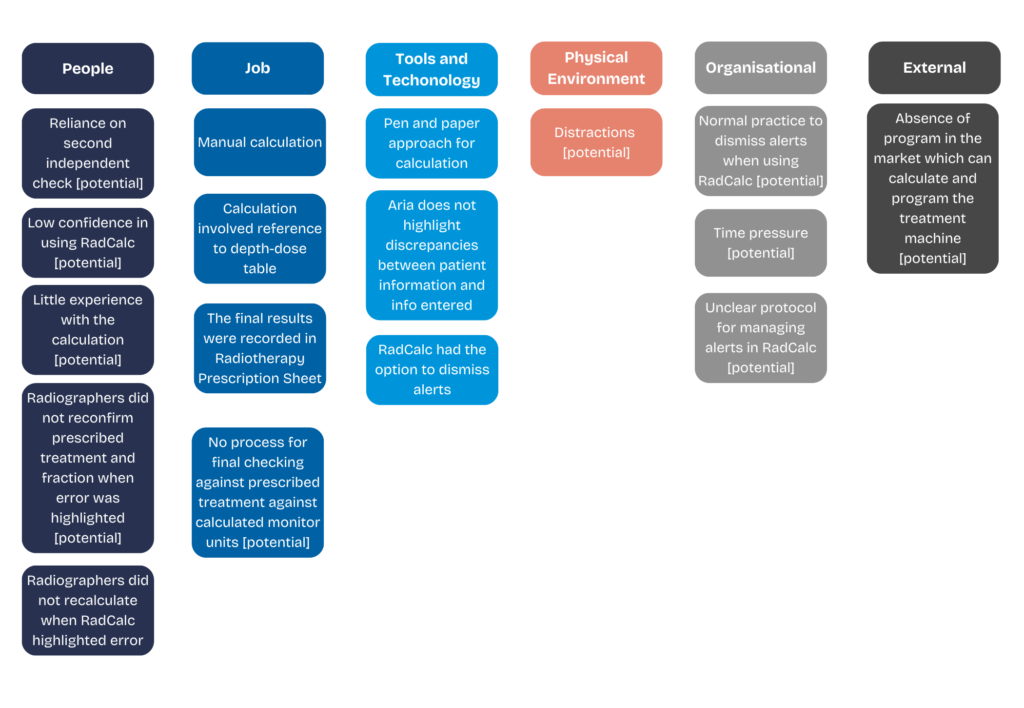

To begin the SEIPS analysis, I extracted information from the sequence of events and categorised them into one of the six categories.

As shown in the table above, the different elements of the event were put into relevant categories:

- People – Actions by the radiographers and the physicist

- Job – How the task is conducted

- Tools and Technology – The tools and programs used by the people in the task (e.g. RadCalc, Aria)

- Physical Environment – Elements relating to the workplace

- Organisational – Information regarding how the team were organised

- External – Elements beyond the organisation’s control

Exploring the Error in Calculation

With the elements categorised, the next step was to consider how the incident could have occurred by examining interactions between these components. For instance, consider the case of the radiographers’ erroneous calculations. The calculations were performed manually, and the results were recorded on a Radiotherapy Prescription Sheet. This pen-and-paper process introduced vulnerabilities. Furthermore, the radiographers had to refer to a ‘depth-dose’ table, which involved looking through a table with various information. This added another layer of complexity.

The absence of early engineering safeguards made it easier for the wrong calculation to go unnoticed, ultimately contributing to an incorrect monitor unit setting on the treatment machine.

In addition to the manual process, there were also other potential factors such as reliance on a second independent check and possible distractions within the work area. Although it is unclear whether these issues directly contributed to the incident, including them in the analysis broadens our understanding of the potential systemic failures.

I also explored other potential factors like the reliance on the second independent check or distraction within the work area. By highlighting these possible factors, we acknowledge that while they were not explicitly mentioned in the sequence of events, they remain important areas to explore in understanding how the error occurred. Hence, it was included in the analysis to broaden our understanding of the potential systemic failures.

Tracing the Erroneous Calculation to the Treatment Machine

The treatment machine was set up wrongly because the (wrongly) calculated units were not adjusted in the RadCalc program. Although RadCalc correctly alerted the users to an error in the entered figures, the radiographers dismissed the alert and even manipulated the programme to align with their manual calculations. This behaviour suggests that the system allows users to override alerts easily, pointing to a possible deficiency in the tool’s design. This might also indicate that it was normal practice within the team to dismiss alerts.

Additionally, when RadCalc flagged the error, the radiographers did not recalculate or reconfirm the prescribed treatment and fraction. It remains unclear whether there was a formal process in place requiring a final verification against the prescribed treatment. The only instance where the prescribed treatment may have been checked was when the information was entered into the treatment planning system, Aria. Even then, Aria was used primarily to export data to RadCalc and did not have the function to highlight discrepancies between the prescribed dosage and the calculated units. This implies that there could be potential organisational and procedural shortcomings within the task.

Interaction of Contributory Factors

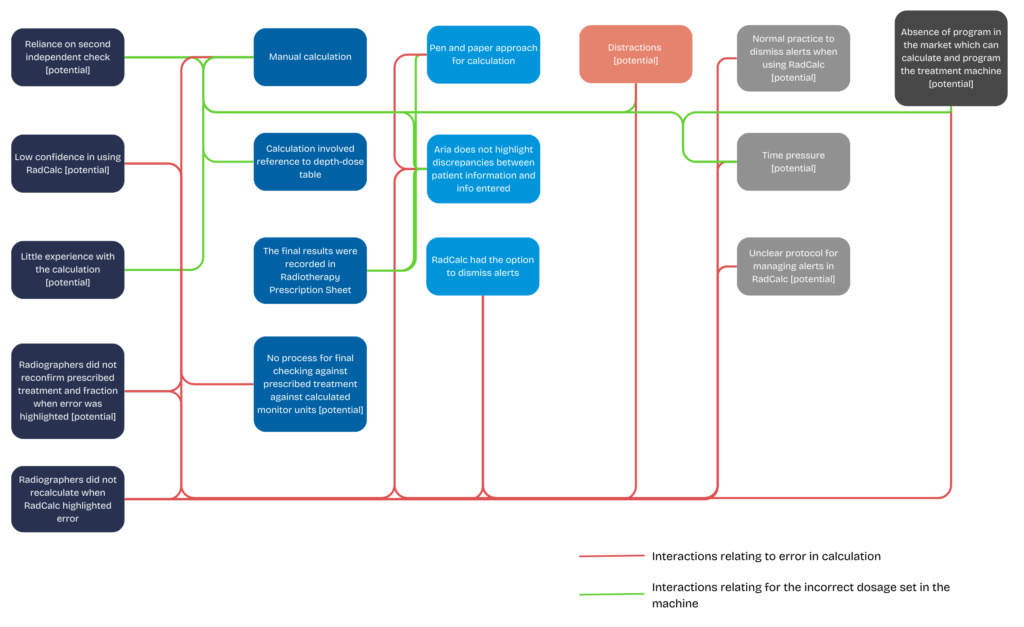

As I unpacked the various potential contributory factors, it became evident that the error was not the result of a single failure but rather the interaction of several systemic vulnerabilities. The illustration below shows how the manual calculation process, overriding the alerts in RadCalc, and possible organisational norms regarding alert management link to create an environment where such an error could occur.

By demonstrating how these factors are linked, we can easily consider possible improvements such as reducing the reliance on manual calculations by implementing automated dose calculations, improve the design of RadCalc so to reduce any possible alert override, and having additional safeguards by having the treatment planning software (e.g. Aria) integrate with validation checks to flag potential discrepancies.

Conclusion

Applying the SEIPS framework to this case study reveals that errors in healthcare are rarely isolated events. Instead, they emerge as a result of the interactions between individuals, the workplace, and the organisation. By breaking down the interactions between these elements, we better understand why errors occur and how they could have affected the individuals’ actions, rather than simply identifying a single point of failure.

My colleague, Steve, wrote a series of blog on safety culture within healthcare. Click here to read the first part of the blog.

Learn more about Human Factors for Incident Investigation – express your interest in our upcoming Learning from Incidents course.