Do you always check your blind spot when you pull away from the side of the road? Do you check you’ve got your keys before leaving the house? Do you double check you’ve got the correct holiday dates before booking?

Checking is important for everyday life but can be critical in safety critical contexts.

There’s more to checking than meets the eye!

Take the blue pill and be confident we know that a check is better than no check, and that two checks are better than one.

Take the red pill and we’ll see just how far this rabbit hole goes.

Observing checks in healthcare

In a previous life, I was a researcher at university doing fieldwork work on hospital wards on medication safety, observing and talking to doctors and nurses about how they worked, their challenges, what was working well and what was not. I have all sorts of stories from this experience, but scouring the memory vault for #checks might be a good place to get this blog started:

One of the standout memories in this area was the goldfish check. This was the term used by some of the nurses by someone holding up a bag of saline from afar, a clear bag of liquid, and checking it’s saline. The goldfish reference was tongue in cheek to make the point that at that distance all the nurse checking could really do is see it didn’t have goldfish in. So there are different degrees to checking and double checking, and they come at a cost, to disrupting someone else’s work.

The checks weren’t all as blasé as this. Some were extremely thorough. For example, when a new nurse was on the ward their work might get more attention than someone more experienced, or when a drug was being administered that was particularly potent or critical then that might get more attention. So, people adapt their behaviour based on perceived risk. One problem is sometimes these perceptions are misplaced as saline can be confused with other drugs and even experienced nurses can make a slip or a lapse error.

Sometimes extra checks are done when the person or system is being scrutinised, sometimes related to what people call the Hawthorne effect. For example, I had been observing a deputy ward sister who was doing everything by the book, which wasn’t a surprise as someone in her position. But after I came back from lunch I observed her waving someone off who asked her for a second check, the message was not to worry about it.

A different hospital recently had the CQC in and the ward I was observing on was one of the ones that had been criticised. So everyone was adhering to checks there… even checking the flushes, used to clear the cannular before the bag or syringe was added, and I hadn’t seen any other hospital do this before. But they deemed, maybe rightly, that there was risk here to be managed, as these flushes could be confused with other things.

I said ‘everyone was adhering to checks’ but that’s not quite right… one nurse threw her arms up in the air in despair one day, and basically said ‘forget it’ in some colourful words, as she couldn’t get a second person to check and just didn’t have the time to be doing it. It was impractical and she caved in under the pressure of work.

At a different hospital the extent to this impracticality really hit home when two nurses were talking at a nurse station one morning, one reporting to the other what an impossible night they had experienced. They had 12 patients to look after between two of them as another nurse was off and their bank staff (supply staff) hadn’t turned up. They’re meant to double check all intravenous infusions, and on top of this they had two ‘specials’ who were patients that required one on one attention. It was just impossible. And so trade-offs had to be made.

If all this sounds extreme, I didn’t even get to talk about the poor lady who hadn’t had any nutrition for over a day. She had an NG tube placed ready for the artificial feed, but it hadn’t been checked by X-ray. This was a new rule at the time as a patient in another hospital had the feed pumped into their lungs as the tube was placed incorrectly. So, they needed to check. She waited the first day but wasn’t seen by the time the radiographers had gone home. The second day she was waiting again… many hours passed and when the doctor found out the length of wait, he went bananas with this requirement to check, which was blocking her feed, which was significantly impacting her health.

What does the research say on double checking in healthcare contexts?

The evidence around double checking of medications shows mixed results regarding its effectiveness in preventing errors. A systematic review by Koyama et al. (2020) found insufficient evidence that double checking versus single checking was associated with lower rates of medication administration errors or reduced harm. While double checking is widely implemented based on an assumption it will reduce errors, the reality appears more complex.

A key distinction highlighted in several papers is between independent double checking and primed double checking. Independent checking requires two people to separately verify information without sharing details that could bias the second checker, while primed checking involves information sharing between checkers (Pfeiffer et al., 2020). The independence of checks appears critical – when one checker primes another with information, it can lead to confirmation bias and reduce error detection.

Practical implementation challenges exist even when policies mandate independent double checking. A study by Milic et al. (2023) identified several key barriers through focus groups with ICU nurses:

- Geography/layout issues making it difficult to find a second checker

- IT system limitations

- The routine nature of checks leading to complacency

- Complex processes and competing priorities

- Personnel factors like experience level and workload

Westbrook et al. (2021) found that while compliance with mandatory double checking policies was high (over 90%), truly independent double checks were rare, occurring in only 1% of administrations. The authors found no significant association between double checking and medication errors when it was mandatory. However, when nurses chose to double check medications that didn’t require it, there was a small but significant reduction in errors.

The evidence suggests several key considerations for checking practices:

- The process needs to be truly independent to be effective

- Practical barriers need to be addressed for consistent implementation

- Technology and workflow design should support rather than hinder the checking process

- A more nuanced approach may be needed rather than blanket double checking requirements

- The substantial time and resource costs need to be weighed against benefits

This synthesis of the research indicates that while checking medications is important for safety, current double checking practices may not be achieving their intended benefits. A more evidence-based and context-sensitive approach to medication checking policies may be warranted.

Written with Claude AI 3.5 Sonnet.

Reflecting on checks in the Process Industries

Now, I do most of my work in oil, gas and chemical plants. Nearly every task we look at involves checks and second checks. If there is a manual check of some critical variable or an action involved in a critical task, then you want some form of check or (re)check to reduce the likelihood of it going wrong.

But another manual check isn’t always the answer. They’re certainly easy to add in a workshop or while sat at a desk reviewing an incident or near miss. The reasoning is: If one person can’t get it right, then let’s have another checking they do.

The worst case I’ve heard of this addition of an additional check involved seven checks of the same thing (although I am sure that every time I tell the story I might add another check to make it sound more dramatic). But something was going wrong, prone to error, even with a second check it went wrong, so they added a third, then a fourth and so on. Story has it that they got up to seven checks before they thought that there must be another way.

Here we come to reflect on the quality of checks, rather than the quantity of checks.

Part of the problem with the above scenario is that all the checks were done together, there was no independence. So there was a crowd of people all checking at the same time, probably presuming one of the others in the group was checking properly so they didn’t have to.

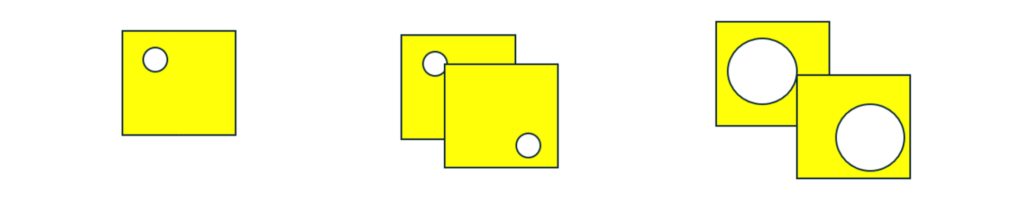

If we try to understand this through the Swiss Cheese Model (Reason, 2000) then the slices of cheese are linked. By adding all these checks, we are adding more slices with bigger holes. Ideally these checks would be independent, so we have more slices with smaller holes. Two checks are not necessarily better than one.

Are two checks better than one?

- Generally perceived wisdom is that ‘two are better than one’, as the second one acts as a catch or safety net.

- However, this is not always the case, as there is a ‘dependency’ between the checkers. The first assumes the second will be good, so doesn’t do it properly. The second presumes the first did a good job and doesn’t do it properly. So, neither is checking properly.

What does the research say on multi-person checking?

The paper by Robson and Robinson (2018) examines checking practices in the nuclear power industry, specifically comparing the effectiveness of single-person versus multi-person checking. Here are the key findings:

Methodology:

- The researchers studied checking practices at several nuclear power facilities in the UK

- Used a mixed-methods approach combining observational data, incident analysis, and experimental studies

- Examined both routine operational checks and safety-critical verification procedures

Key Findings:

- Counter to common assumptions, multi-person checking did not consistently outperform single-person checking for error detection

- The quality of the checking process was more important than the number of checkers

- When two people were involved, the effectiveness decreased if:

- One person deferred to the other’s expertise

- There was social pressure to agree

- Both assumed the other person would catch any errors

The study identified several factors that improved checking effectiveness regardless of whether one or two people were involved:

- Clear, standardized procedures

- Minimizing distractions during the checking process

- Active engagement rather than passive verification

- Regular rotation of checking pairs to prevent complacency

- Proper training in checking procedures

The authors note important differences between nuclear and other industries:

- Nuclear industry has more standardized processes

- Greater emphasis on independent verification

- More structured training in checking procedures

- Different time pressures compared to healthcare

Recommendations from the authors suggest:

- Focus on improving the quality of checks rather than simply adding more checkers

- Develop clear criteria for when multi-person checking is truly necessary

- Invest in training and standardization of checking procedures

- Consider using technology to support or replace human checking where appropriate

Conclusion:

This paper’s findings challenge the common assumption that two checkers are always better than one, suggesting that the quality and independence of the checking process may be more important than the number of people involved. These insights could be valuable for healthcare organizations considering their checking policies.

Written with Claude AI 3.5 Sonnet.

Terminology

There’s a lot of terminology in this area so it’s good reflecting on this to know what we’re talking about, and to survey the landscape of checking:

- Single check: One person verifying information against a source, with no second person involved in the process, and is sometimes referred to as a “solo check” or “independent verification.”

- Double check (variant 1): Refers to two complete verifications of the same information done by two people and is often used as an umbrella term for various two-step verification processes.

- Double check (variant 2): Refers to where there are two bits of information to corroborate rather than one, e.g. instead of just checking the name of a patient you might check their date of birth as well.

- Double check (variant 3): Refers to one person verifying the same information twice, e.g. they check something when they collect it, and then just before use they check it again.

- Second check: Refers to verification by a second person, though this may or may not be conducted independently, and is sometimes used interchangeably with “double check” despite having this distinct meaning.

- Independent double check: Two separate verifications conducted without sharing information between checkers, which can be performed either by one person doing two separate checks or two people checking independently, and is specifically designed to avoid confirmation bias.

- Primed double check: When the second checker is given information by the first checker (for example, “Can you check this is morphine 5mg?”), making it more prone to confirmation bias, and is sometimes called a “prompted check” or “collaborative check.”

- Concurrent check: Two people checking simultaneously, which may be either independent or primed, and is often used for high-risk procedures requiring immediate verification.

- Sequential check: Refers to verifications performed one after another, which can be done by the same or different people, and allows time between checks for fresh perspective.

A recent case study on checks and checking

Charging reactors is a common task for small batch processing chemical sites, i.e. this is where operators need to put chemicals into a container so some sort of chemical processing or reaction can take place. If there is a mischarge an unintended and uncontrolled reaction could take place. Often this can involve charging drums, kegs and powders of different chemicals.

In a recent Human Factors Safety Critical Task Analysis (SCTA) study we were able to examine checks before charging in some detail.

There were checks and second checks when receiving the material to site, there was a pre-assembly stage where there were additional checks, and check and second checks before charging.

To try to make these checks more robust we thought of several principles and practices that would strengthen the reliability of checks:

| Negative influence | Positive influence | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Passive checks, e.g. just initial | Active checks, e.g. write down the pressure |

| 2 | Right at the end when everything is already done | Involved in the process |

| 3 | No formal clear second check documentation, e.g. maybe just an initial on the side of the page | Clear formal documentation to explain what you are checking and signing against (date and time) |

| 4 | Not independent (same time, place and people doing it together) | Independent as possible (different time, place and people involved) |

| 5 | Not auditable | Auditable |

| 6 | Roles and responsibilities mixed | Clear roles and responsibilities |

| 7 | The thing being checked is hard to check and easy to confuse, e.g. handwritten note | The thing being checked is easy to check and hard to confuse, e.g. controlled document |

An important part of this work was that we weren’t trying to take a behavioural approach to get operators to be more careful, to focus and concentrate even harder, we were trying to engineer and design better sustainable checking procedures.

Some key points in the work included:

- Bringing the second check before charging from the end of the process to the middle. This meant that the person at the end wasn’t just parachuted in to provide a signature, but they had more involvement… something could be awry and their check would be scrutinised by the next person.

- Trying to properly document the checks. One second check was well documented, but improvements could have been made on a new second check that had been introduced.

- Having two bits of information to check on the same product.

- Removing the use of handwritten notes in favour of controlled printed documentation

- Considering a check point as a gateway to another stage of the process, where someone has the responsibility to clear the product through the check point, along with documentation and some physical action if appropriate so they have some tangible act, e.g. removing red tape.

Another important principle is the notion of ‘active linking’ in checks so the person checking has to interact to perform the check rather than passively initial, tick a box or press OK (Henderson & Cross, 2005). Henderson and Cross (2005) write:

| Active linking Where several items must be checked, a major error mode is an incomplete check. For the charging process under review, this is the failure to check every drum to be charged. If it is possible to actively link the check action to each object being checked, this should significantly reduce this likelihood. As an example, the procedure could physically require operators to interact with each object to be checked in the following ways: – Every container has a unique identifier to be recorded prior to charge. – Operators must remove/add something from/to each container. However, with this approach, there is a potential danger of introducing complex systems that require extensive resource to maintain and that could introduce new error modes. This approach should be followed with caution and a consideration of the whole system. Henderson & Cross (2005) |

By the end of the study it felt like we had a better clarity around the different checks, how each was organised and what role they played in contributing to a safe and reliable process. We spent a lot of time at a fine-grained level talking about the structure and organisation of these checks, aided by the Safety Critical Task Analysis (SCTA) process. The Hierarchical Task Analysis (HTA) broke down the steps of each check into a step-by-step approach, the failure modes and PIFs (Performance Influencing Factors) were employed to think about what could go wrong and where, and the workshop with Human Factors knowledge and practical experience really made this all come alive.

Summary

Checking is a critical human activity for detecting and correcting errors, especially in safety-critical industries. However, not all checking is equally effective. This blog post has explored the nuances, challenges and best practices around checking through several lenses:

- Personal experiences observing checking practices in healthcare settings

- Research evidence on the effectiveness of double-checking for medication administration

- Reflection on checking practices observed in the process industries

- A recent case study examining checks before charging reactors in a chemical plant

Key insights include: (1) the quality and independence of checks matter more than the quantity; (2) practical challenges can undermine the consistent application of checking procedures; (3) human factors engineering can systematically improve the design of checking procedures through practices like active engagement, clear documentation, separation of checks, forcing functions, and simplification; (4) technology may support checking but can also introduce new failures; and (5) checking is a sociotechnical activity that requires considering the complex interplay of human behaviour, tools and technology, processes and culture.

In conclusion, this deep dive into checking has revealed it to be a deceptively complex activity. By understanding the human and systemic factors that influence checking performance, we can engineer more reliable and resilient checking processes. However, we must remain vigilant to the ever-present gap between work-as-imagined and work-as-done. Continuous monitoring, learning and improvement are essential for keeping pace with the dynamic realities of safety-critical work.

Active engagement, clear documentation, and clearly defined responsibilities are examples of what we call positive Performance Influencing Factors (PIFs). In another blog, Dom discusses the benefits of using positive PIFs for SCTAs. Click here to read more about it.

The SCTA process is an analysis methodology that prompts organisation to evaluate risk from a human, design, and engineering perspective. Our team of established consultants are highly experienced in SCTAs and can support you with improving your processes. Get in touch with us today by emailing [email protected]

References

Henderson, J. & Cross, S. (2005) Human checking failures in the chemical industry – how reliable are people in checking critical steps? Paper presented at World Congress of Chemical Engineering, Glasgow 2005.

Koyama, A. K., Maddox, C. S., Li, L., Bucknall, T., & Westbrook, J. I. (2020). Effectiveness of double checking to reduce medication administration errors: a systematic review. BMJ Quality & Safety, 29(7), 595-603. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009552

Milic, V., Cameron, L., & Jones, C. (2023). Identifying barriers and enablers for a robust independent second check of medication in adult intensive care. British Journal of Nursing, 32(17), 840-848.

Pfeiffer, Y., Zimmermann, C., & Schwappach, D. L. B. (2020). What are we doing when we double check? BMJ Quality & Safety, 29(7), 536-540. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009680

Reason, J. (2000). Human error: Models and management. BMJ, 320(7237), 768-770. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768

Robson, S. E., & Robinson, S. J. (2018). Single- and multi-person checking: Are two really better than one? Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries, 56, 412-421. Examines checking practices in the nuclear power industry, providing valuable cross-industry insights.

Westbrook, J. I., Li, L., Raban, M. Z., Woods, A., Koyama, A. K., Baysari, M. T., Day, R. O., McCullagh, C., Prgomet, M., Mumford, V., Dalla-Pozza, L., Gazarian, M., Gates, P. J., Lichtner, V., Barclay, P., Gardo, A., Wiggins, M., & White, L. (2021). Associations between double-checking and medication administration errors: a direct observational study of paediatric inpatients. BMJ Quality & Safety, 30(4), 320-330. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011473