I’ve been lucky enough to be invited to contribute a chapter in a book about Near Miss Management across different sectors. I’ll mainly be discussing the application of Human Factors Safety Critical Task Analysis (SCTA) for investigating near misses for Process Safety related concerns.

This will be informed by ideas behind the SHERPA methodology (Embrey, 1986), instantiated in the SHERPA Software and experience in applying SCTA on near miss investigations.

While thinking about the chapter, I wanted to share these early ideas and request feedback from you, the reader. You’re obviously interested enough to read this blog, hopefully you’re interested enough to let me know your thoughts, e.g.:

- Are these novel ideas or not to you?

- Are they described well?

- What do you like, dislike and what am I missing?

Constructive comments and criticisms are most welcome.

If you also had stories to share about near misses that I could anonymize and use in the chapter that would be most welcome too.

Anyone who responds with some useful info along the lines of the above, by email, will be sent an early review copy of the chapter: [email protected]

1. Organisational Learning: Perception-Action Cycle

Don Norman published his Perception-Action Cycle in 1988. It outlined 7 stages, from perceiving the world to acting upon it. According to the model you first perceive the world, you then interpret those perceptions, and then evaluate them. Based on this evaluation you will then think of a goal. After this, you will form an intention, plan actions and then execute the planned steps.

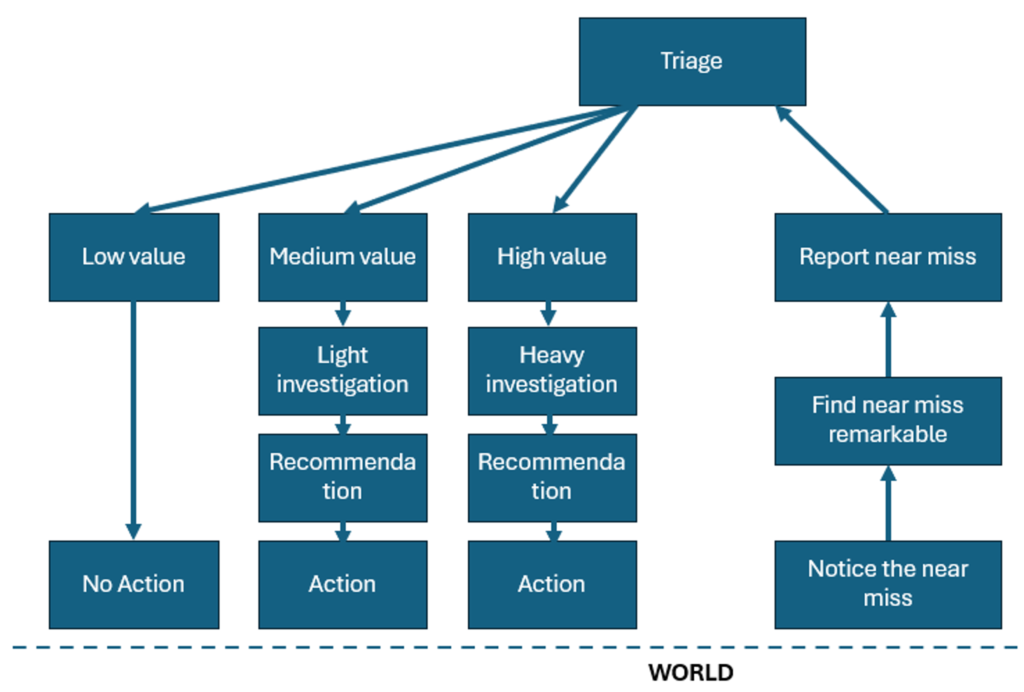

For Near Misses, most organizations seem to work on a model which relies on 1) a reporting system, 2) some sort of triage to decide what to do with the near miss, and then 3) investigation. If anyone had some formal procedures or further information on this it would be great to see.

The Perception-Action Cycle could be thought about from an organisational perspective when thinking about near miss management, with a bit of expansion and tweaking of course.

1. Reporting

Reporting is depicted on the right-hand side of the diagram. The first step in the model is to notice a deviation has taken place. Some deviations could go unnoticed if, for example, the consequences are not realized until later, or an error is recovered quickly and so insignificant it barely registers in the conscious mind. If a deviation is noticed then whether people find it remarkable is the next consideration. Again, if an error is quickly recovered or insignificant, then it may be considered unremarkable (Furniss et al., 2011). If it is remarkable then a decision will need to be made about whether to report it or not. Cultural norms and expectations, the ease of reporting, rules and procedures, perceived cost and value, and perceived risk to others and themselves will all play a role in whether an individual will decide to report the deviation or not.

2. Triage

Incidents and near misses will be collected in a reporting system. These reports will then be triaged. This could be done in different ways but could be influenced by the potential value of investigating the incident or near miss for organizational learning, and the potential severity of the consequence if, for example, the near miss had led to an unwanted outcome.

In the triaging system we have represented, there is not just a simple yes or no decision on whether the incident should be investigated, but a decision whether not to investigate, whether to investigate in a light way, or whether to launch a full investigation.

3. Execution/Application

The investigation process should lead to some learning and recommendations. These will need to be communicated and considered before remedial actions are taken. Of course, depending on the quality of the investigation things could be missed, learnings might not be deep enough, and wrong conclusions could be drawn.

Does this look like your near miss management system?

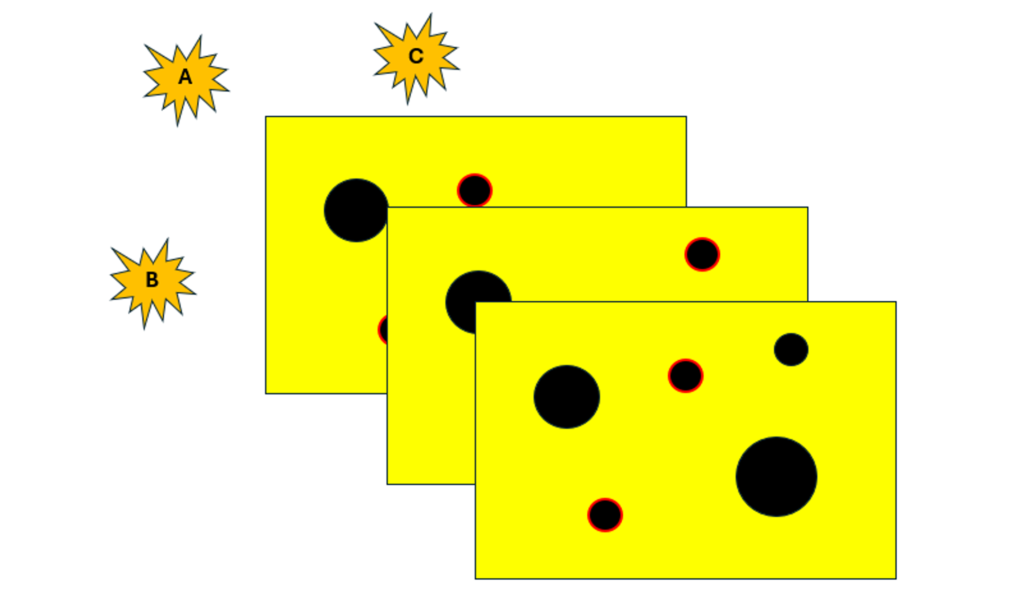

2. Swiss Cheese Model: Types of Near Miss

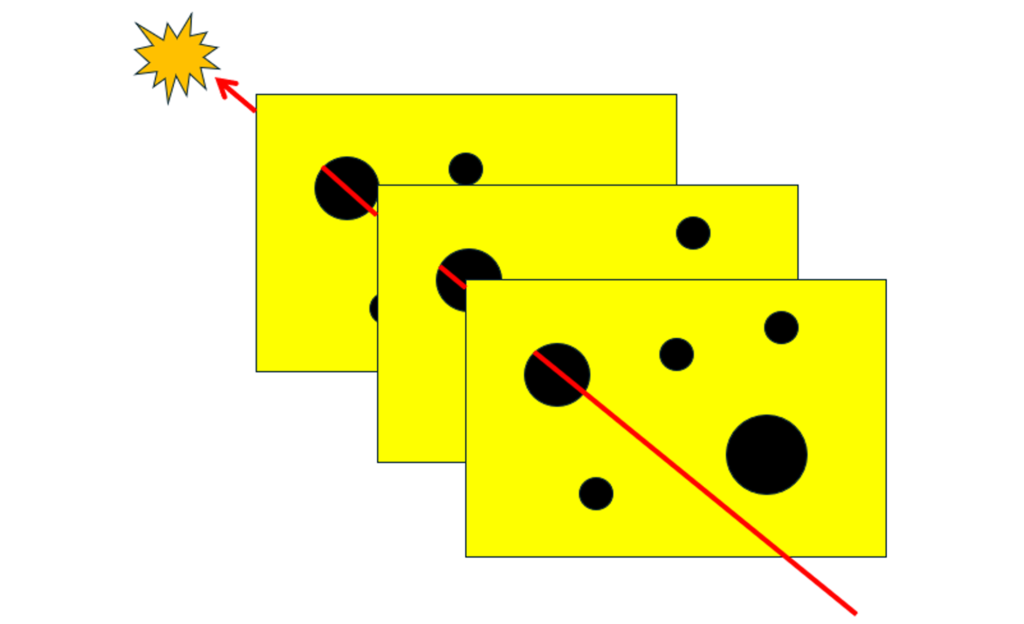

The Swiss Cheese Model (Reason, 2000) depicts successive layers of defence, barriers and safe guards. These layers of defence might be imperfect due to latent conditions and active failures, which are depicted by holes in the barriers. This looks like swiss cheese hence the name.

These holes do not need to be static. The more barriers and less holes, the less likely something unwanted will be able to work its way through. Something unwanted could occur when the holes come into alignment – in reality this could be a series of unwanted events and vulnerabilities that interact to defeat a system.

When we think about near misses, we can use the Swiss Cheese Model to think of different types of near misses.

Some refer to the difference between failing safe and failing lucky.

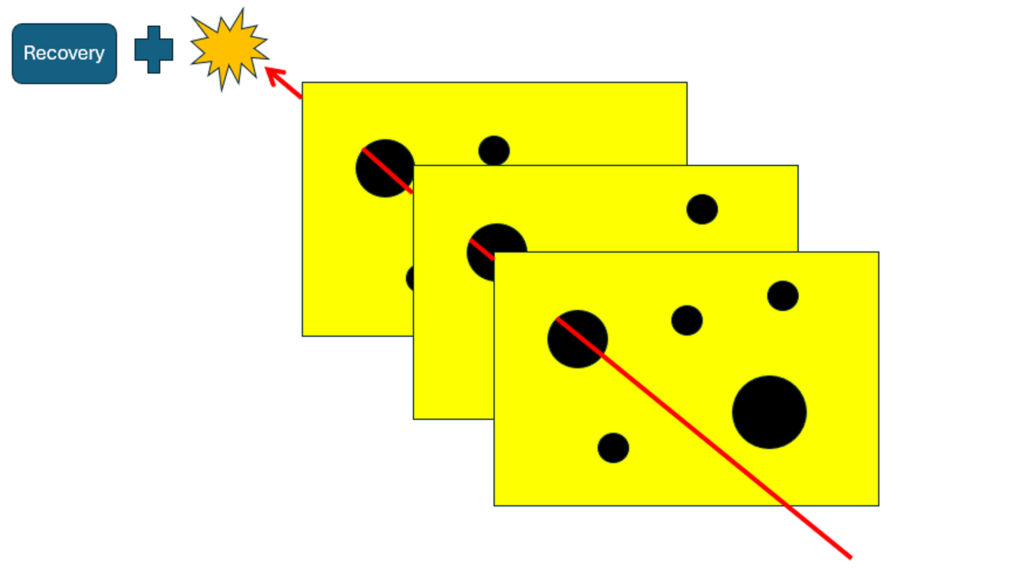

We might consider a near miss to have failed safe if the final consequence was not realized because one of the barriers or safeguards worked and protected the rest of the system. For example, the calculations on filling a tank were incorrect, there was no supervision, the operator did not respond to the high level alarm, but the high level trip stopped the filling, which prevented the overfill.

We might consider a near miss to have failed safe if the final consequence was not realized because there was an effective recovery. For example, smoldering was seen coming from part of the plant. Quick thinking by the operators meant this did not escalate into fire or explosion, but the safeguards and barriers to prevent this were defeated.

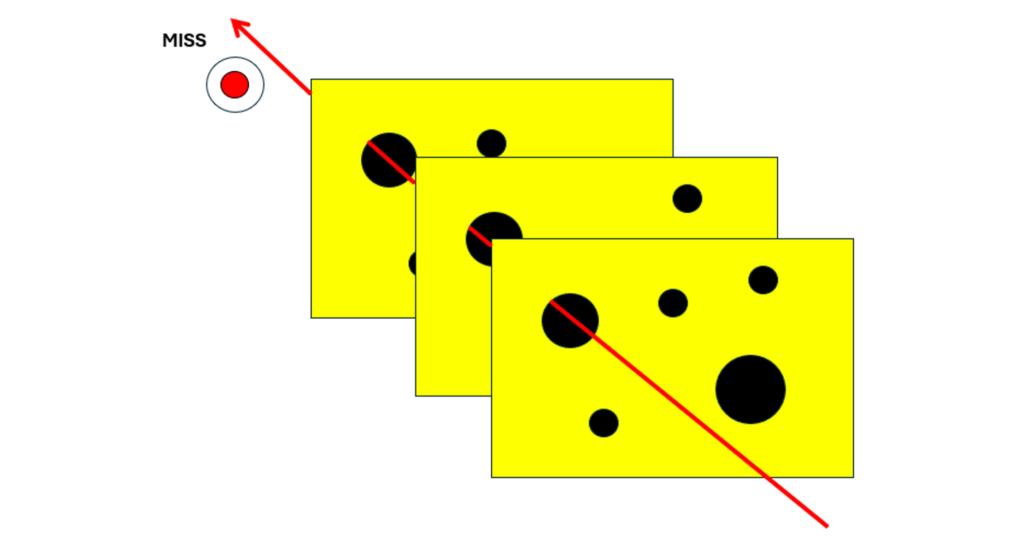

We might consider a near miss to have failed lucky if the controlled barriers and safeguard failed but the cost or harm was not realised just because of luck. For example, a heavy load fell from scaffolding and the only reason it didn’t kill anyone is because no one was around.

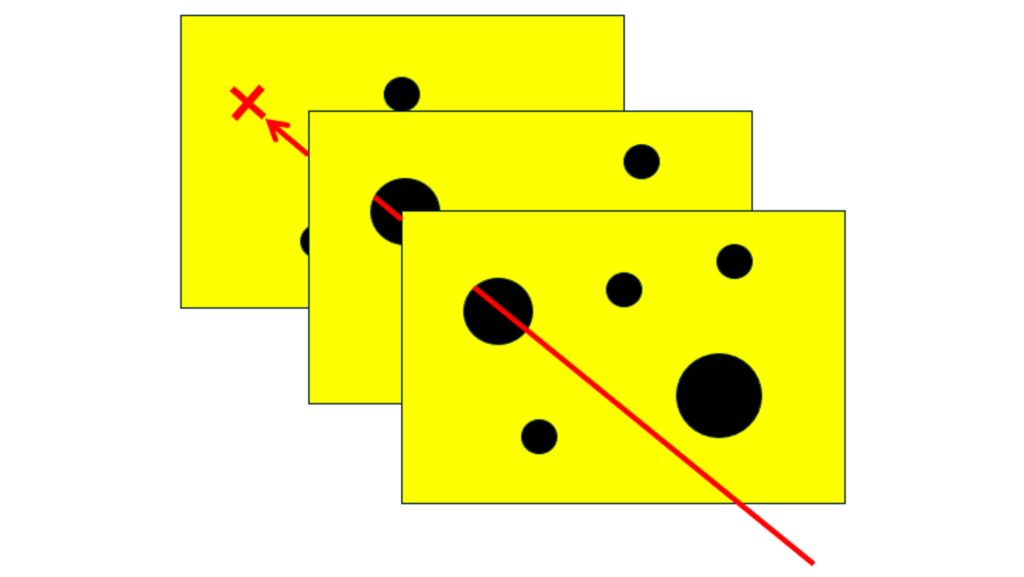

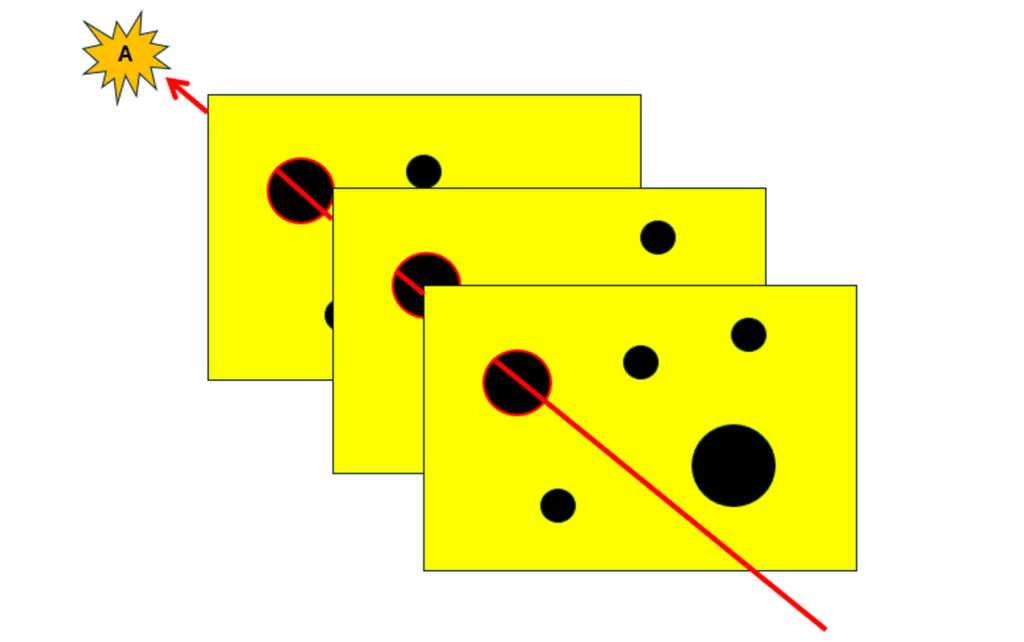

3. Swiss Cheese Model: Types of Investigation

The Swiss Cheese Model can also help us think about different types of investigation.

The typical type of investigation will be most interested in establishing the specific event sequence that led to the accident. This will focus on the holes that came into alignment and the outcome that drew attention to these events in the first place. For near misses it would be the potential outcome that did not quite happen for some reason. One criticism of this approach is that there are other holes and vulnerabilities in the system that have not received review and attention.

A broader investigation might seek to try to reveal and review the other holes and vulnerabilities in the system, which could be related to multiple unwanted outcomes. This is similar to a proactive approach to human factors assessment, like SCTA, as we’re investigating the potential for failure and its consequences before these events have come into play.

Arguably the broadest approach for maximum learning for investigation is to combine these approaches. Here we have a reactive approach by attending to the specific incident sequence, and a proactive approach by attending to pathways that did not lead to the incident, and pathways that could lead to other unwanted outcomes.

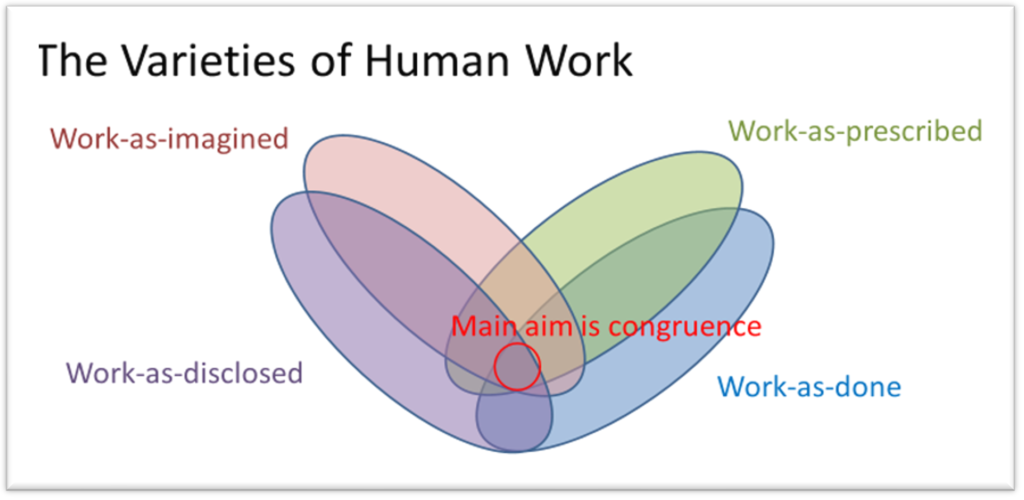

4. Threaded Enquiry: Multiple theories, Lines of enquiry and Events-as-X

In a similar way that we can use the Work-as-X framing to think about the role of different perspectives on work for SCTA, we can use Events-as-X to think about handling near misses. This sort of thinking has been inspired by Steve Shorrock who manages an excellent Human Factors blog over at Humanistic Systems, e.g. https://humanisticsystems.com/2020/10/28/proxies-for-work-as-done-1-work-as-imagined/

4.1 Events-as-imagined

For incidents and near miss events, we must appreciate that we may never know what really happened or what was going on inside the heads of the individuals involved. For serious accidents, people may no longer be available to tell their stories. For those who remain, they may not share the whole truth for fear of litigation and punishment. As analyst we are always one or two steps removed from the events that actually took place.

Furthermore, understanding incidents and what to do about them can be fraught with biases. One of the worst offenders is the knee jerk reaction to blame and reprimand the person closest to the failure: proximity bias. This needs to be called out and recognized, treated as a theory, while other theories are also entertained.

Theories should be actively generated and explored. These could be driven by data and narratives from the incident, e.g. perhaps other members of staff also report that operating a by-pass in the way it was done is common practice, it could also be driven by the analyst asking about ‘what if’ scenarios and exploring lines of enquiry. Here imagination can play a positive role in the investigation.

Imagination and different lines of enquiry could be driven by considering different Failure Modes, and a library of Performance Influencing factors (PIFS). This was covered in a previous blog on incident investigation, so won’t be repeated here.

4.2 Events-as-done

This is how events of the incident or near miss actually unfolded on the day, but could include the weeks and months that shaped the latent conditions leading to it. Only the people involved will know what really went on, but even here their memories may fade, be recreated, and their perception might not be completely objective.

It’s often the job of the incident investigator to find out exactly what happened, establish the sequence of events involved in the incident, and find the root cause. However, as referred to above, this could only be a subset of the interesting vulnerabilities and potential outcomes that are inherent in the system.

4.3 Events-as-prescribed

Sometimes it may be useful and interesting to think about how the events should have been done, and why that wasn’t so. But we need to be careful here and falling into counter-factual thinking and attributing blame. This is where the investigator or team of people trying to understand and act on an incident start to anchor their thinking around an idealized scenario that did not happen, that generally everything would have been OK just as long as the person followed the rules and did what they were told, but they didn’t, and so we had the bad outcome. They should have known better. However, it doesn’t do justice to why the behaviour and events actually unfolded as they did, i.e. events-as-done. For example, perhaps the messy reality meant that not enough time was given, it was common practice to override the by-pass, that there were many nuisance alarms, the training didn’t cover the scenario or that there was a spike in work and the team were completely overloaded.

It can, however, be useful to think about how things should have unfolded to identify missing steps and opportunities for recovery that didn’t happen. If we only focus on what did happen then it can be hard to identify these omissions. These should be treated as separate lines of enquiry, further theories to be entertained and learn from.

4.4 Events-as-disclosed

Like any analysis, the quality of it is dependent on the data. When damage and harm occur the organization may open a window of opportunity to learn, investing resources to analyze the incident and find out what went wrong to ensure that it doesn’t happen again. However, the people involved may have already closed ranks to protect the team or themselves, making it harder to learn.

Some argue that embracing a fully proactive approach is beneficial because we can learn about system vulnerabilities and potential incident paths before anything goes wrong.

Near misses have an important role to play if embraced by the organization, as hopefully no major harm has been suffered, but yet it is a signal of what could have happened. This should hopefully trigger an investigation opening up different lines of enquiry.

5. Summary

This blog has introduced different ideas around the topic of near misses.

- Firstly adapting the perception-action cycle to think further about how near misses are heard and acted upon by an organization.

- Using the Swiss Cheese Model to think about different types of near misses and whether people fail safe or fail lucky.

- Using the Swiss Cheese Model to reflect on the scope of investigating near misses, i.e. is it just the incident sequence that is of interest, different pathways to the same outcome, or system wide vulnerabilities that could lead to a multitude of different outcomes.

- Applying Events-as-X as a framing for thinking about constructive narratives, entertaining theories and investigating lines of enquiry about a near miss.

These are some of the early formative ideas I’d like to weave into my chapter on near misses. It would be great to hear your thoughts on what you think is useful, novel, what needs to be clarified and what might be missing.

If you email me, I’ll make a note to send you an early review copy of the chapter.

It would be great to hear from you, and even if you had stories of near misses that I could potentially anonymise and share for the chapter.

Email me here: [email protected]

Learn more about Human Factors for Incident Investigation – express your interest in our upcoming Learning from Incidents course.

6. References

Embrey, D. E. (1986). SHERPA: A systematic human error reduction and prediction approach. In Proceedings of the international topical meeting on advances in human factors in nuclear power systems.

Furniss, D., Blandford, A., & Mayer, A. (2011, July). Unremarkable errors: low-level disturbances in infusion pump use. In Proceedings of HCI 2011 The 25th BCS Conference on Human Computer Interaction. BCS Learning & Development.

Norman Donald, A. (1988). The design of everyday things. MIT Press.

Reason, J. (2000). Human error: models and management. BMJ, 320(7237), 768-770.