What are PIFs?

Performance Influencing Factors (PIFs) are factors that can increase or decrease the likelihood of human error occurring. Negative PIFs increase the likelihood of error; positive PIFs decrease the likelihood of error.

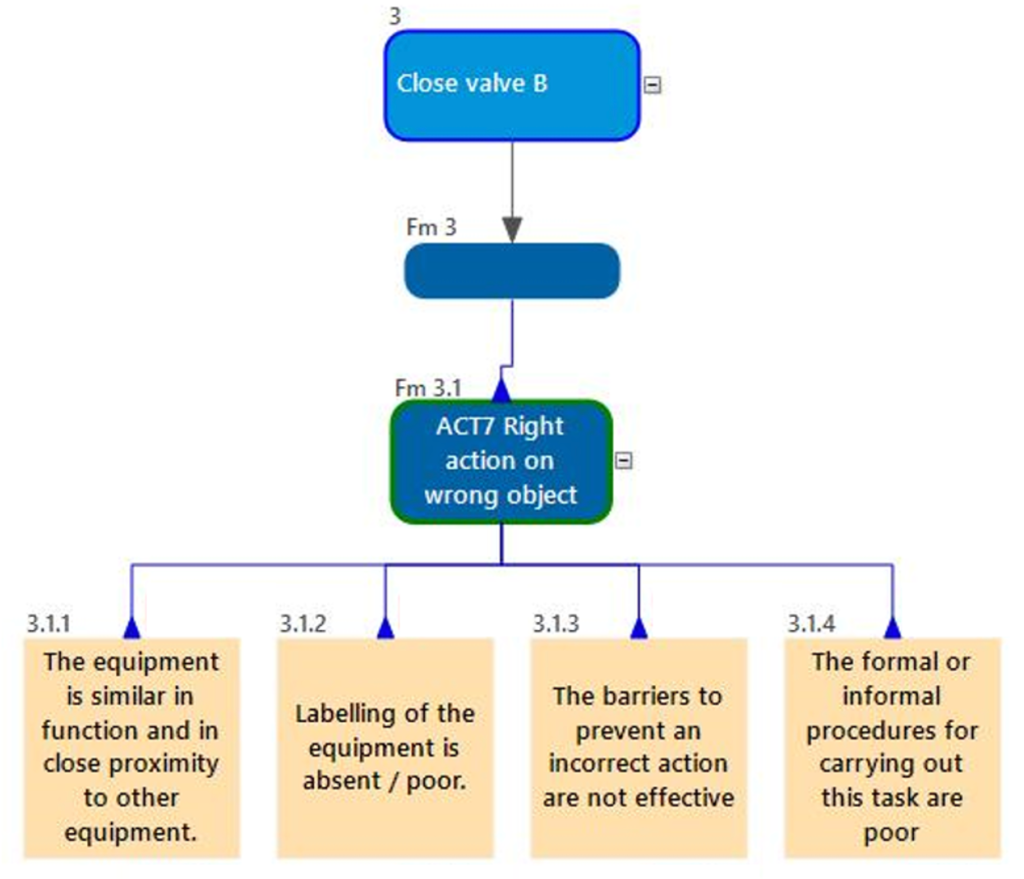

As an example, say we wanted to avoid confusing two valves. The more negative the PIFs the higher the likelihood of failure, e.g. if the valves are not labelled, look the same and they’re close together the likelihood of confusing them could be high. At least it will be higher than if the valves are labelled well, look very different and are physically far apart.

The role of PIFs in Human Factors Risk Assessments

In Human Factors risk assessments, like Safety Critical Task Analysis (SCTA), we assess the quality of PIFs and their influence on different failures. Where we find deficiencies, we try to think of measures to fix and optimize them, to reduce the likelihood of potential error. For example, we might suggest that the labelling of valves is improved.

We can also identify what is already good about the way the system is organized and how it behaves. This balances our understanding of risk, as looking at both the positive and negative PIFs gives us a more holistic view of the likelihood of error. It also allows us to recognise, protect and reinforce features in the system that already play a role in reducing error. For example, if we’re concerned about confusing two bags of white powder and one bag is 6kg and the other is 12kg, then this greatly reduces the likelihood of confusing. We don’t want the procurement department to start buying bags that are both 12kg because they can get a better deal, as this could introduce the potential for error.

“Should Positive PIFs be included in the risk assessment?”

Recently a client asked me whether positive PIFs should be included in the Human Factors risk assessment. We were working through an analysis together and I had noted a positive PIF, I can’t recall what it was now, but he had been challenged on it previously and wanted to gauge my response.

It’s not the first time that this question has come up and so I thought it was worth addressing in a blog.

We think including positive PIFs are useful for two main reasons:

- A richer holistic view: If we want to understand and assess risk in a rounded way then we should include positive and negative PIFs for the full picture, not just one side. If the site has some good practices and reasons why we think this error is less likely to happen, then should we omit that data from our analysis, and leave that part blank? Or should we include it? We think significant and interesting positive aspects of the system should be part of the analysis to show these elements have been discussed, considered and accounted for.

- Resilience and reinforcement: One of the problems with only looking at the negative aspects in the system is that we might be missing opportunities to learn from normal work and how things already go well (which resonates with Safety II thinking for those interested in that).

- (a) Reinforcing system strengths: If there are positive ways the system is organised then we want people who manage the system to understand and appreciate this. It may be that these arrangements and conditions are challenged in the future and we want their positive role to be considered and protected. For example, perhaps management decide that one operator can do a job rather than two, maybe procurement change supplier and now the two different coloured drums now look the same, maybe a paper checklist that can be easily ticked off with a pen is now digitised making it harder for the operator to keep track.

- (b) Resilience strategies: If there are informal positive behaviours in the system then these too might be worthy of noting and building into the procedure. For example, one shift might do things slightly differently to the others which makes them more resilient to error. A colleague of mine was training a Pharma organisation in the US. When discussing errors and frustrations one of the shifts brought up misplacing filters when they were removed as part of a procedure. Someone from a different shift immediately recognised their pain and frustration, this is something that also annoyed them and recurred frequently. Someone from a third shift did not know what they were talking about, “Why don’t you use the bag?”. “What bag?”. “We use a bag to put the filters in and then we just replace them at the end.” This resilience strategy was unknown to two of the shifts. Recognising this informal behaviour means that we can build it into the procedures and the training, making it more formal and benefitting system performance overall.

N.B. We agree that positive PIFs should only really be used where they are significant, and that good procedures and well trained operators who know what they are doing should be avoided as positive PIFs, otherwise most sites would claim these two for every step in the task. Given the focus on critical steps and major accidents, most attention will likely be given to fixing vulnerabilities in response to negative PIFs, but positive PIFs do have a role to play as argued above.

Examples of Positive PIFs

To give more of a flavour of positive PIFs we describe two here that have come up in client studies:

- The client was concerned about mischarging a reactor with the wrong powdered chemical. There were four reactors which we will call A, B, C and D. They all looked the same and next to each other. Next to the reactors, the four different chemicals were kept in white bags that looked quite similar A, B, C and D. The main concern was putting bag A into reactor B, or bag B into reactor A. Assuming the operator worked with all four bags and all four reactors, the PIFs were looking quite negative for this highly manual task. However, there was a strong positive PIF in the way that work was organised. One department worked with reactor A and bag A only, another department dealt with the other 3 reactors and bags. This division of labour made the error much less likely.

- Another organisation did not want to confuse two different drums. A positive PIF here was that just under 4 drums were needed for this particular process, so the operators would use a new pallet of 4 drums every time, which were still wrapped in plastic from delivery because it made them easier to transport. This greatly reduced the chance of mixing up a drum of the other chemical which is typically used as single drums only.

Positive PIFs and Safety II

In recent times, there has been growing interest in the distinction between Safety I and Safety II. Safety I is characterised as a find and fix approach to safety, focusing on what could go wrong and how, and then addressing those flaws to manage risk. In contrast, Safety II is more concerned about how safety is created in a complex world where circumstances and failure paths cannot be predicted, so resilience abilities need to be fostered so the system has adequate adaptive capacity for whatever is thrown at it.

Safety I is meant to focus on understanding failure and how to avoid it.

Safety II is meant to focus on understanding normal work, how safety is created and adaptive capacity.

Some mixture of both is needed. Indeed, some have argued that the distinction is a false one and that mature approaches to Human Factors and safety have done this all along.

Our argument in this blog, i.e. to consider positive PIFs, is much closer to the Safety II end of the spectrum than Safety I. This seems especially so when considering factors that already enhance and create safety but they are not fully appreciated or acknowledged by those in the context. We want these positive features to be recognised in normal work and enhanced.

From Resilience Strategies to Formal Controls

In our usual Human Factors risk assessments, like SCTA, formal controls are already recognised. So if some feature of the context is already contributing to safety then shouldn’t it just be listed as a formal control?

Listing something as a formal control is quite clear when it is a strong engineering control like a high level trip on a storage tank. However, it can become less clear when talking about weaker administrative controls: where these are strict like a fully independent check and sign-off this seems more like a formal control, however a second pair of eyes to monitor the process could be considered more of a PIF.

Clearer examples of positive PIFs might be clear labelling (rather than poor labelling) and a good HMI (Human Machine Interface) (rather than a poor one).

As discussed above, sometimes different operators and shifts might have innovative practices compared to others that help improve their performance and reduce error. These are not yet formalised controls, but their practice could be recorded as a positive PIF, a way to help reduce the likelihood of error.

In a previous life, I used to do research into informal resilience strategies, which can help improve performance and reduce error. A bit like doing a four point check before leaving the house so you don’t forget those items, leaving something by the front door so you collect it when you leave, or maybe differentiating keys on a bunch so you’re less likely to confuse them.

We used to call the act of creating a resilience strategy from new ‘Big R’. This could include an operator innovating a new strategy to reduce error, e.g. putting filters in a bag so they are not mislaid, as in the example described above.

We used to call the act of adopting or adapting a resilience strategy ‘Little r’. This could include one shift learning from another, e.g. learning that putting filters in a bag will reduce the likelihood of losing one.

Once these informal resilience strategies were recognised it seems beneficial to design them into the system, to formalise them, through design, procedure and training. However, by doing so they no longer become informal, they have crossed some divide between a less formal influencing factor to a formal control. This crossing is not always obvious, sometimes it is a grey area, and for the purposes of the risk assessment and analysis it is probably more important acknowledging it somewhere rather than worrying too much about what box it goes in.

Devil in the detail

Just like for negative PIFs, positive PIFs are often at their most powerful when they are detailed and linked to specific failure modes. For example:

- Rather than just saying +ve METHOD, say +ve METHOD: Practice of collecting filters in a bag so they are not misplaced

- Rather than just saying +ve WORK DESIGN, say +ve WORK DESIGN: Different departments work on different reactors

In our analysis we use symbols to differentiate positive and negative PIFs, using +ve and -ve respectively. We will also start a new line for each PIF, and capitalise the label, which helps us to differentiate the PIF information, making it more readable.

There are different lists of PIFs. One of the most well known is the list of PIFs provided by the HSE. The SHERPA software has a more detailed library of PIFs that actually vary by the failure mode that is selected. In both cases it is important to contextualise the PIF assessment by adding more detail to the PIF label. Just listing categories of PIFs is too generic.

Summary

Positive PIFs can play a useful role in Human Reliability Assessments (HRAs) and SCTAs by helping us attend to normal work, how safety is created and error avoided. Arguably, it provides a more balanced approach to understanding risk than solely focusing on the negative aspects. It can help elicit positive features of context, and more informal controls and behaviours. These informal features can be acknowledged and protected, and informal positive behaviours can be shared and formalised.

We agree that positive PIFs should be used sparingly, and that positive PIFs based on good procedures and competences should generally be avoided.

Hopefully this blog will help people think through some of the potential benefits that come from considering positive PIFs.

Come on our flagship SCTA course

If you’ve enjoyed this discussion and want to have more opportunity to learn more than come on our flagship course on Human Factors Safety Critical Task Analysis (SCTA). Find out more here: https://the.humanreliabilityacademy.com/courses/human-factors-SCTA

Further reading on resilience strategies:

- Furniss D, Back J, Blandford A. Resilience in Emergency Medical Dispatch: Big R and little r. To appear at the WISH Workshop, CHI; 2010.

- Furniss, D., Back, J., Blandford, A., Hildebrandt, M., & Broberg, H. (2011). A resilience markers framework for small teams. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 96(1), 2-10.