This post builds on Steve’s previous blog Safety culture? What’s the point?, which talks about organisational culture and the link between safety culture and safer outcomes.

There are many ways that organisations develop, retain, and share knowledge. Some of this knowledge will concern technological developments or emerge from research. But in the management of safety, there are two main routes: reactive and proactive. In this post, I look at what a healthy reporting culture looks like and how this can develop organisational knowledge, and how that contrasts with a proactive approach to risk and safety.

“Culture” and “error” in the 21st Century

“Culture is a slippery term, which can be either trivial or momentous. … In one sense it is what we live by, the act of sense-making itself, the very social air we breathe; in another sense it is far from what most profoundly shapes our lives1.”

This slippery quality, where “culture” can signal so many things, means that we need to define our focus. Here, I am interested in two attributes of an organisational culture that we can try to pin down: how an organisation responds to and learns from problems (its “maturity” in this regard); and how this works in practice – in the day-to-day lives and practices of staff, safety managers and general management – the reporting culture, in fact.

“Error” has also become a slippery term, too. It’s probably fair to say that today, most workers in safety do not see “error” as an individual, bounded event or act. Instead, we are constantly aware of the context in which error occurs – the social, cultural, local context – and error is usually seen as a window through which to view wider systems.

Working in safety-critical industries, some of us will be aware of the theoretical and cultural difficulties in understanding error, especially “human error”, but whatever our perspective, when something goes wrong we have responsibilities in mitigation (how can we make this better) and in prevention (how can we stop this happening again?) which require a pragmatic approach. This means that the way an organisation responds to information about systems, errors, failures or all types is significant.

Pathological? Bureaucratic? Generative?

So, how can we evaluate organisational maturity? One way was set out by Westrum. Starting with the view that organisational culture bears a predictive relationship with safety and that particular kinds of organisational culture improve safety, Westrum2 examined how organisations managed and applied information and information flow. This relates directly to the ability of the organisation to learn from all aspects of its operations but especially its ability to learn from errors and other problems.

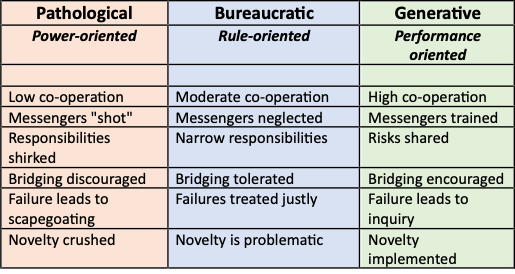

Westrum described three dominant cultural types—pathological, bureaucratic, and generative. In this model, these types are shaped by the behaviours of leaders – the workforce then responds, creating the culture. Key characteristics are illustrated below.

Many readers will be able to identify some of these characteristics in organisations or teams they have worked in. From my own experience in the healthcare sector, I would say that most staff see their organisations as Bureaucratic3, for example. How do you see your own?

Westrum’s typology formed the basis for a further cultural tool developed especially for the healthcare sector – see box 1.

Box 1 – MaPSaF

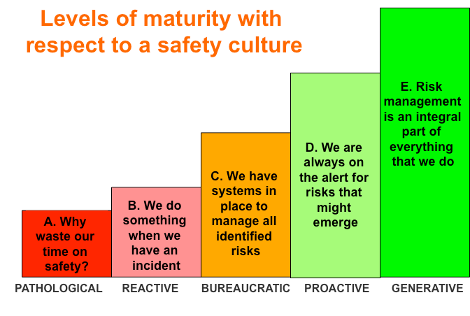

MapSaF (The Manchester Patient Safety Framework)4 extended the typology of Westrum to five organisational types, shown below with one example description to illustrate each type.

MaPSaF is usually used, not as a measure, but as a framework to start and support conversations about safety in a team – a safety intervention, a way to raise awareness. There are versions of MaPSaF designed for acute medicine, primary care and other sectors, each with detailed descriptions of characteristics in a range of dimensions.

How do these cultural types relate to organisational learning? Well, consider that a major (sometime the only) element in the way we manage safety is through our response to things going wrong. In healthcare, for example, staff are expected to report errors, near-misses and risks they have identified in their work in the expectation of fair treatment and genuine change (see my last blogpost). In the NHS, this is the very essence of the safety strategy – and has been now for two decades. Despite this, we know from news reports and whistle-blower reports that “messengers are shot” – metaphorically, of course. Why is this?

Reporting culture in the 21st Century

Reporting and analysis of incidents is, of course, a reactive approach to safety. It isn’t the only, or even the best, way to identify safety interventions – at this consultancy, for example, we have advocated for a proactive approach to safety in healthcare to complement incident review for a very long time. But as it stands, healthcare, like many other sectors, relies on reporting. So what does reporting culture look like, today, more than 20 years since An Organisation with a Memory5?

At HRA, we have developed and applied a model of learning through reporting. There were some things – in the culture or the systems, or matters of attitude or belief – that needed to be examined squarely. For example, what are the dominant beliefs about error and blame in the organisation? And do managers and staff hold the same model of error? Is the actual reporting system – the physical manifestation of policy – usable? Does it routinely capture systems and human factors? What are the real-world consequences for people who report errors? Does it affect job prospects or security? Or is everything alright: do people report freely, without fear of consequences, in the expectation of change and improvement?

Our model of a reporting culture

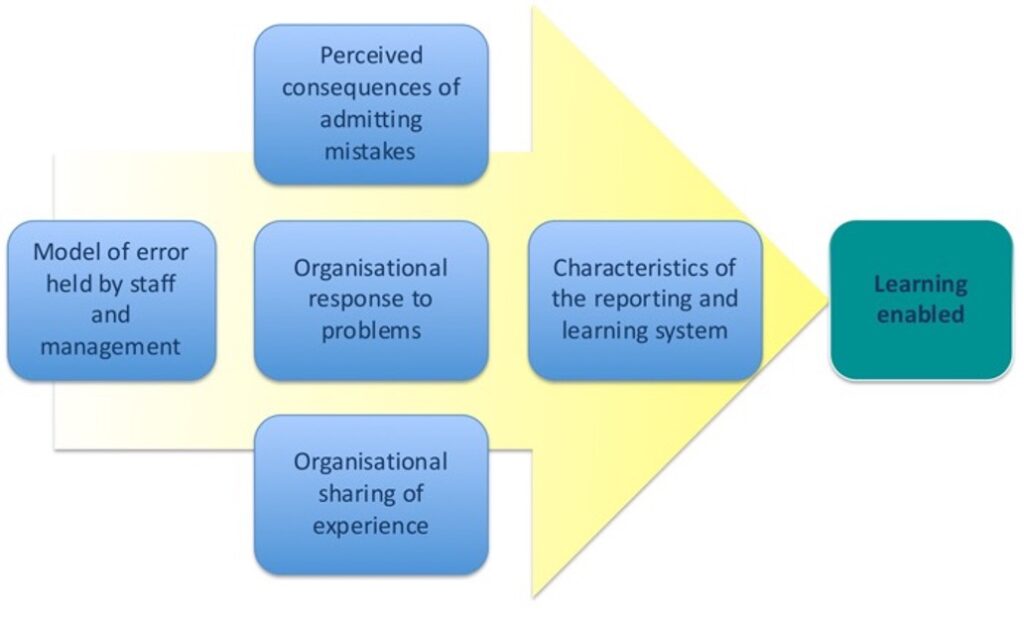

In summary, a healthy reporting culture requires that:

- The organization must hold a model of error which sees errors as learning opportunities

- The organization must manage the perceived consequences of reporting error for individual members of staff

- It must respond to reported problems

- It must motivate sharing of experiences

- And have an incident reporting system with good usability and support.

The model, illustrated graphically below, shows how reporting and learning works in practice, and comprises five “scales” or “dimensions”, each of which is necessary in enabling learning.

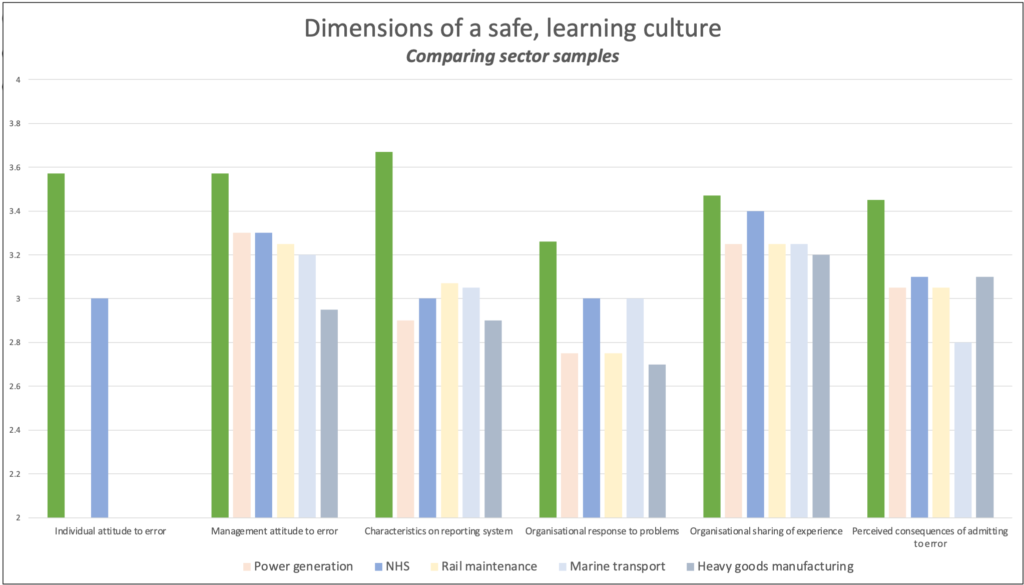

We evaluate these dimensions with a 60-point survey tool and check our validity and the reliability of the scales. The chart below provides some example findings from various sectors. Some data from recent studies are not available to share, but we can see that most sectors score around the mid-point of the scales.

On this scale, a score of 3 indicates the mid-range, with higher scores indicating a positive culture of learning. Take a moment now and ask yourself where you would expect your organisation to be for each of these items…

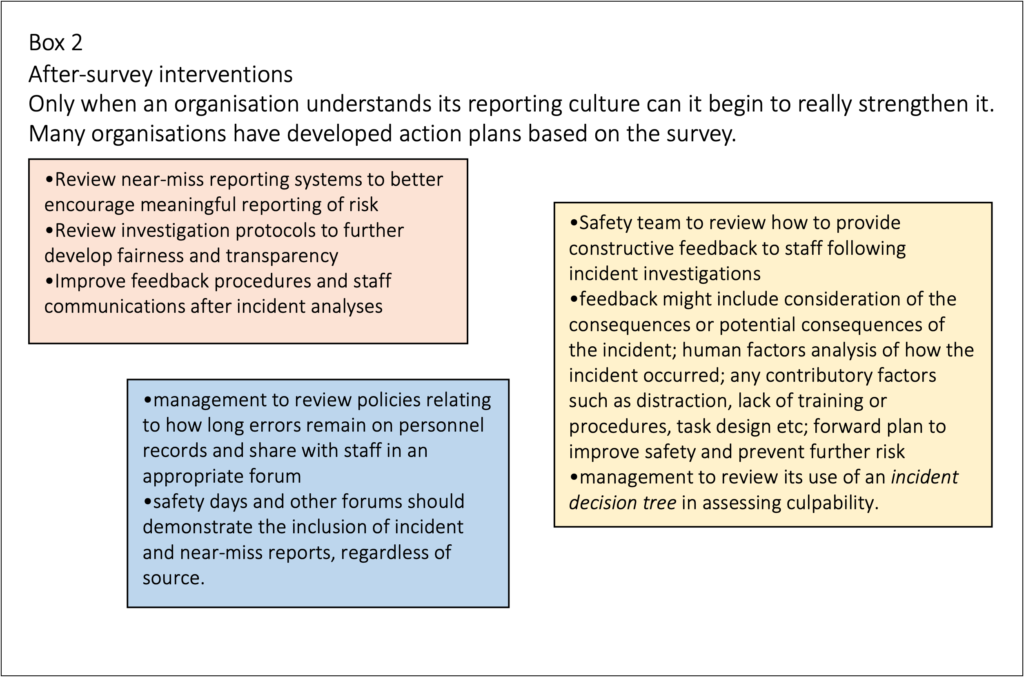

Does this indicate a healthy reporting culture? Not really – that would need scores in the 4-5 range – though it doesn’t necessarily mean that culture is “pathological”, either. What it does indicate is that, in general, attitudes to error still include individual blame, that reporting systems are mediocre, organisations don’t share experiences or respond to problems in such a way to motivate staff, and that the consequences of reporting an error can adversely affect your career. Much of this reflects the perception of “psychological safety” in the organisation. See box 2 for examples of management interventions that often follow the analysis.

If your organisation’s safety management depends on reporting, you might want to ask yourself how it might perform here – in fact, ask this: can you rely on your reporting culture in managing safety?

Well, can you?

In the next blogpost, we will describe a further tool for evaluating and improving the response of pharmaceutical manufacturing plants to Corrective and Preventative Actions (CAPAs), where errors and failures can be leveraged to improve efficiency, safety and regulatory compliance.

HRA previously played a leading role in supporting the Safety Clinical Systems initiative. To read more about the project, click here.

HRA offers human factors consultancy services to support Human Factors in the healthcare industry. To learn more about how we can support you, click here.

References:

- Eagleton, T. (2003). After Theory. Basic Books.

- Westrum, R. (2004). A Typology of Organisational Cultures. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13(suppl_2), pp.ii22–ii27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2003.009522.

- Spurgeon, P., Sujan, M., Cross, S. and Flanagan, H. (2019). Building Safer Healthcare Systems: A Proactive, Risk Based Approach to Improving Patient Safety. Springer.

- Parker, D., Kirk, S., Claridge, T., Lawrie, M. and Ashcroft, D. (2007). The Manchester Patient Safety Framework (MaPSaF). Patient Safety Research: Shaping the European Agenda – International Conference Porto, Portugal.

- Donaldson, L. (2002). An Organisation with a Memory. Clinical Medicine, 2(5), pp.452–457. doi:https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.2-5-452.