In the heart-pounding world of Formula 1, the phrase “life on the limit” once carried a chilling connotation. Formula 1’s early years were fraught with danger, prompting a paradigm shift from accepting risks to drivers, stewards and the crowds, to embracing system changes and safety enhancements. This transformative approach is equally relevant to industries such as process safety, oil, gas, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals, each with its unique challenges and risks. The key message is that we should focus less on individual performance, errors and the acceptance of risk, and more on systemic changes and risk management.

Two Contrasting Incidents

“Life on the Limit” is also the name of a great documentary that has inspired this post. In that they contrast the state of Formula 1 in the 1950’s with more recent incidents.

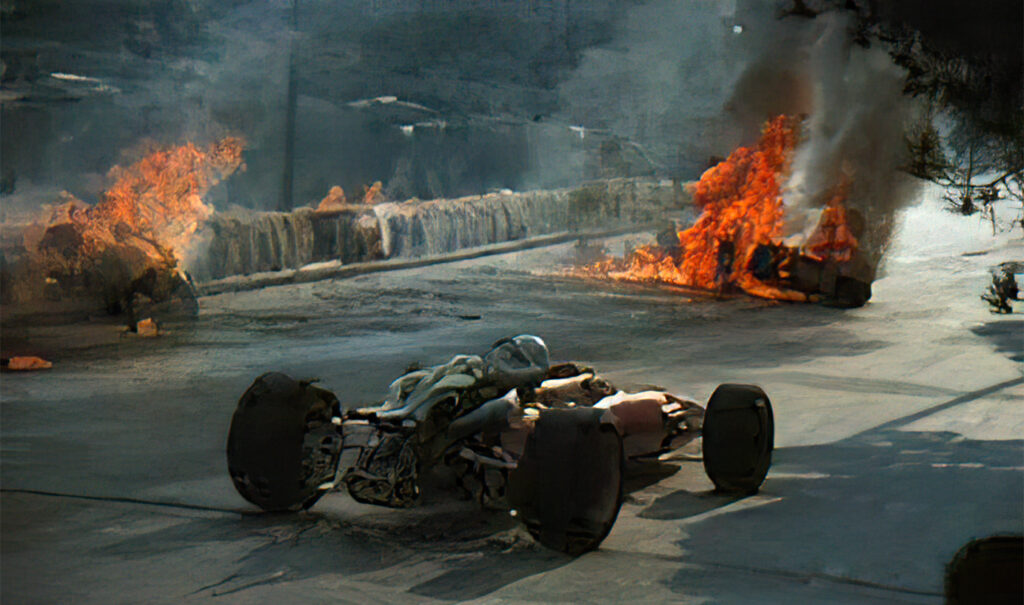

The documentary shows old footage of Lorenzo Bandini racing in Monaco in 1967. It’s obviously an older looking car, the cameras are slightly shaky as they try to follow the car around the roads, he goes round one corner and then another, and the car explodes.

It’s not possible to tell what happened exactly, other than some debris goes into the nearby water and the upside down car is engulfed in a cloud of flames and fire. The camera focuses on the car, the commentators shocked. Other cars swerve around the vehicle as they continue the race. A steward races towards the flames and the commentators hope that one of the fire crews might be nearby. The race continues. There are no signs of life or escape.

You can view a video of the crash here.

This is in contrast with footage from a frightful crash involving Marting Brundle in Australia, 1996. Shortly after the start of the race, amidst the bustling traffic, the yellow racing car flies into the air, tumbles across the gravel, wheels and debris flying everywhere. It did not look survivable, the car was at rest after tumbling over and over. The stewards rush over. We wait for signs. And then Martin Brundle appears, looking at the car, it seems he is as shocked as everyone else that he has walked away from the crash. He feels OK. He turns to the track to see they have stopped the race and his mind switches, that’s convenient he thinks, he’s got time to get the spare car and he runs off to join the race again.

What has changed?

Is this step change in safety and performance because we now have better drivers? Better training?

No.

The drivers are surely similar, in terms of peak human performance.

Then what?

There have been massive changes to the system, which include…

- Inherently safer design of cars to protect drivers, lower the likelihood of them bursting into flames.

- They’re changed processes, for example the race will now stop when there has been a crash whereas before it would just continue.

- They have a surgeon on site at every Formula 1 event, with more stewards and procedures ready for an emergency response.

- They have run off areas, gravel traps and crumple barriers all designed to bring the speeding car to a safer stop.

- PPE has got better, e.g. Romain Grosjean jumped out of a flaming car at Bahrain in 2020 with burns to his hands but the rest of his suit protected him in the flames before he got out.

You can view a video of the crash here.

What brought these changes about?

Two other great documentaries and dramas that complement “Life on the Limit” are “Rush” and “Senna”. All three together give a more complete picture about why these changes happened. What encouraged or forced people to change direction and follow a different path, as there is always inertia in any organisation or practice… we’ve always done it this way around here mindset.

A sociologist once said in a presentation that the very idea of an institution is about resisting change, protecting itself, and remaining stable.

TV was a big reason. As Formula 1 became more popular it became unpalatable to watch people dying on TV. They had to bring in changes as it became more mainstream. Audiences also worshipped drivers, like Senna, and so his death was mourned by thousands, also not a good look for the sport.

There was also some heroic leadership. Some drivers stood up for safety. Quite often safety first is a wishful slogan used by management rather than a meaningful commitment. Lauder practiced this when he refused to race in the pouring rain, he lost the championship, but he won respect by sticking to his principles and trying to encourage better appreciation of driver safety, rather than the default option that was to risk life and limb for glory.

Piper Alpha was a huge turning point for safety regulations in the UK. This well-known disaster spurred changes to separate safety oversight from production pressures… and opened the door for a different approach for managing human performance and human error. After some big nuclear and industrial disasters people were fed up of reading about human error as a cause and so they wanted to take steps to reduce risks before accidents happened. This opened the door to Human Factors and system safety concerns.

A structured approach to Human Factors

The UK has a structured approach to applying Human Factors for Major Accident Hazard (MAH) sites, which fall under the COMAH regulations. This approach is enforced by the UK regulators, the HSE. They inspect in line with 6 topics:

- Managing Human Performance

- Human Factors for Design

- Critical Communications

- Procedures design and management

- Critical Competencies

- Organisational issues

These 6 topics cover a system of safety affecting the likelihood of human failure.

The UK offshore regulators now have their own related inspection guide, which is very much aligned to these 6 topics, but they divide them up differently, so there are 13. Other regions like Singapore and Brazil also seem to be on the path to implementing similar rules, regulations and changes. Some large multinational sites are also pursing this path as bets practice in human performance management.

You can find out more about this approach to Human Factors in our course Introduction to Human Factors for Process Safety, Loss Prevention and COMAH:

https://the.humanreliabilityacademy.com/courses/hf-plc

Human Reliability Associates

Human Reliability Associates (HRA) has been a leader in this field for many decades. It was established over 40 years ago to look at things like Three Mile Island. Since then, it has developed and promoted Human Factors Risk Management best practice for different safety-critical sectors. We provide consultancy, training and software services.

Sign-up to our email list to receive further information, announcements, blogs and newsletters.