An important element to any real world human reliability assessment is to be aware of different perspectives of work, their limitations, and how these limitations can be overcome to generate effective insight and action.

Distracted and overwhelmed with the nuts and bolts?

When learning about a method we can get bogged down in the nuts and bolts of how to do it.

Do this…

Do that…

Don’t go more than 9 boxes across in the task analysis…

Does this error mechanism suit this failure mode? Are there others?

Especially when a method is new to us, there can be so many different elements to understand and keep track of. New concepts, jargon, rules and advice to follow. We can lose sight of the bigger picture. This can be demotivating. We lose ‘why’ we’re doing it. As the well-known saying goes: we can’t see the wood for the trees.

The bigger picture: Work-as-imagined (WAI) versus Work-as-done (WAD)

The wood, or bigger picture, that I wanted to lean into here is exploring the difference between work-as-imagined and work-as-done. Essentially, we know or suspect there is a gap between how we think work gets done and how it is actually done, but how can we test this and how big is the gap? A gap could seriously undermine our safety management system and compromise human performance.

This higher-level purpose is simple and energising: Do we really know how work gets done? And once we know how we can better support it.

Work-as-imagined (WAI) and work-as-done (WAD) is proving to be a bit of a sticky concept.

People who do our Human Factors Safety Critical Task Analysis (SCTA) course tell us that they are using these concepts and distinctions when they return to base, having conversations about them, and so they start to impact the thinking and discourse within the organisation.

Work-as-imagined (WAI) and work-as-done (WAD) is not a new distinction or concept. I first came across this sort of distinction when doing my MSc through the writings of Argyris in terms of espoused theories vs theories in use. I am sure there are versions of this distinction and imagine they have a deep history. Essentially, what do people say is going on or should be going on, and what is actually going on?

In recent times, and especially in Human Factors circles, people are talking more about Work-as-imagined (WAI) and work-as-done (WAD).

Expanding perspectives on human work – Towards Work-as-X

Steve Shorrock has been developing other perspectives on work. For example we could have work-as-prescribed (the written work instruction could specify how the work is carried out) and work-as-disclosed (what details are people willing to share about the work… information that can sometimes be sensitive, especially if it does not conform to the official rules). You can read more about the different perspectives on work and their detail here: https://humanisticsystems.com/2020/10/28/proxies-for-work-as-done-1-work-as-imagined/

I’m going to refer to these different perspectives on work as Work-as-X, where X captures the idea that we can switch in and out of these different perspectives.

Safety Critical Task Analysis / Human Factors Critical Task Review

For those who are unfamiliar with SCTA, briefly, it is a methodology focused on Human Reliability. You analyse the a task systematically, you anticipate what failures might occur at the different task steps, and then you analyse what factors might increase or decrease the likelihood of those failures. SCTA is widely applied in the high hazard industries, e.g. in the UK it is a requirement for Major Accident Hazard sites, like some oil, gas and chemical sites, to apply this method to their most critical tasks. So the likelihood of human error playing a role in a major disaster is reduced. This methodology also goes by other names and can be applied to improve human reliability for quality and production purposes as well as safety. For a quick overview you can view our FREE 30min mini-course on Human Factors Critical Task Review (HFCTR).

How does Work-as-X apply to Safety Critical Task Analysis (SCTA)?

Indeed, as we’ll see, part of the job of the methodology is managing these different perspectives effectively. Mismanaging these perspectives can lead losses in quality, efficiency and effectiveness of the method.

From Work-as-prescribed to Work-as-analysed

When we do SCTA in practice we usually like to start with a good set of procedures that explains how the task is performed. This is work-as-prescribed. However, the gap between these procedures and how the work is performed can vary. Sometimes there can be quite close alignment and in extreme circumstances they can bear very little resemblance to what is going on. For example, they could be decades old, not updated after plant changes and modifications, and operators may use their own notes and instructions.

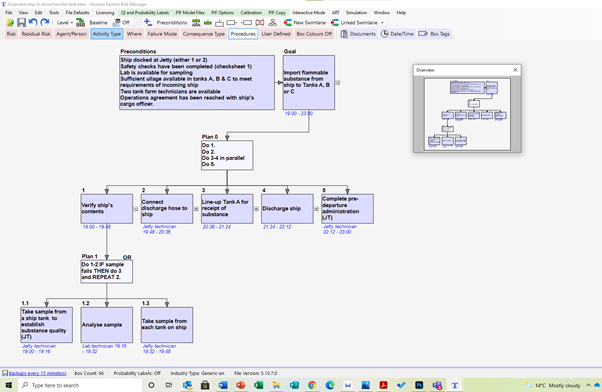

We will do a preliminary task analysis on these procedures. Applying a graphical Hierarchical Task Analysis (HTA) we will transform the procedures into a task representation that can be better understood and interrogated. We rarely find that the task does not change at all once we do the analysis and engaged with operators.

Pitfalls at this stage: It’s rare but we have seen some sites who assume work-as-prescribed is work-as-done. They miss out this analysis stage and transfer the steps to an Excel sheet where they’ll do their failure and PIF (Performance Influencing Factors) analysis. This misses out on the insights that a systematic task analysis might bring and overlooks the discrepancies that can occur between these different perspectives of work.

Work-as-disclosed and Work-as-observed to enhance our analysis

Once we have a good task analysis representation we will run a workshop and a walkthrough, to invite input from frontline staff, safety managers and engineers.

The workshop will try to build rapport quickly and set the scene to encourage people to disclose issues about the task if they exist. This can be challenging in some contexts as issues of non-compliance might be frowned upon and leave the people who do this practice in a vulnerable situation. We’re reliant on staff being open, so we can learn, and feed this data and experiences into the analysis process. This helps close the gap between work-as-imagined and work-as-done.

The walkthrough will involve physically stepping through the task as it is carried out in practice, or as if it was being carried out in practice, so we can see the context and design of the workplace system. This might encourage further disclosures about how the work is performed and issues to do with the work. Sometimes extra thoughts will come to people when they are in the workplace setting that they are used to rather than an office or meeting room that they never visit. There might also be unintentional disclosure as staff struggle to find a valve that they claimed they operated frequently in the workshop.

Pitfalls at the stage: People in the workshop are not given the time or impetus to share divergent views about the task. Instead there is a rush to get the workshop done and close down discussions that might delay the completion of the work.

Work-as-imagined in the risk assessment

Work-as-imagined is often used in a derogatory sense. Afterall, we are trying to get at work-as-done so work-as-imagined usually refers to those who are detached from work and don’t really understand it.

However, I wanted to make a positive case for work-as-imagined in the risk assessment. Once we have done the task analysis we will do a failure analysis (to anticipate what might go wrong) and a PIF analysis (to explore what factors might be increasing or decreasing the likelihood of those errors). In the work we do we use a series of guides words to help us to consider the different types of failure, the psychological mechanisms behind these, and sometimes a library of PIFs to help us explore this space.

In some sense these guidewords help us explore potential events that may not have happened yet – we are imagining events and states that have not yet taken place. So the quality of our imagination feeds into the quality of the risk assessment. But that doesn’t mean we sit back in our armchair and brainstorm away. This is a constructive process, feeding in views from the workshop participant’s experiences, our own experiences as human reliability experts, and with the support of the guidewords.

Pitfalls at this stage: People might not have an optimal system for exploring the different failures and PIFs, hence it is laborious, and as a shortcut for time and effort they only explore a subset of the available failures, e.g. what if the step was omitted or incomplete. This can reduce the depth and quality of the analysis.

Work-as-(re)imagined in recommendations

Once we have an idea about what could go wrong, and the factors driving these failures we can (re)imagine a new design for the task. This might involve reorganising task steps, changing equipment, introducing checks and automation, new labelling and signage. Here we are imagining a new way for people to work so they find it easier to do the right thing, harder to do the wrong thing and almost impossible to do something really damaging.

Pitfalls at this stage: People who are focused on traditional models of human performance and human error can find it hard to imagine how to improve the situation other than through training the individual or rewriting a new set of procedures.

Work-as-prescribed in new SOPs

Through the SCTA or HFCTR process we would have reanalysed the task – hopefully bringing work-as-imagined and work-as-done closer together, we would be more aware where risks are in the task, and so we are in a better place to produce a new set of procedures with comments and warnings.

Pitfalls at this stage: If you’re using Excel or some other manual method for this stage it can be difficult to transfer the information from one system to another, to produce the new SOPs. Through using the Human Factors Risk Manager (HFRM) software we can produce a draft set of procedures from the work above at the touch of a button.

Work-as-trained in competence standards

Specific training for tasks can sometimes be rather general with learning on the job playing a large role. This can be inconsistent and could potentially miss important details. Now we know where the most riskiest steps are given all the good work we have done above. We can now elicit knowledge and skill requirements to perform those critical task steps correctly.

Pitfalls at this stage: Again, if you’re using spreadsheets and doing your SCTA and HFCTR more manually then you’ll be hindered by the work involved in moving the information from one place to another. The Human Factors Risk Manager (HFRM) software has another template which can take the headache out of this work.

Key questions for considering Work-as-X in your context

- What different perspectives of work are there?

- How well do they align?

- How can we improve their alignment?

- How can we use these perspectives to manage work more safely and with better outcomes?

Human Factors SCTA is an approach that can take you through these perspectives of work and manage them in a systematic way to improve human performance.

Take your next steps to improve safety and human performance…

If you’re new to this methodology you can get a quick overview here: FREE 30min mini-course on Human Factors Critical Task Review (HFCTR).

If you want more thorough training in this area then have a look at our flagship SCTA course, which is accredited by the CIEHF: Human Factors Safety Critical Task Analysis (SCTA) course

If you’re interested in the SHERPA Software (formerly known as the Human Factors Risk Manager (HFRM) software) and how it can help you apply a practical approach to Human Factors then have a look at the link and get in touch with us to find out more.

We’ll hopefully be producing more blogs soon so sign-up below to be the first to hear about them